Renewable liquid heat fuels sustainability in higher learning

A world-renowned college in New York’s Hudson Valley region is converting from natural gas to a renewable liquid heating fuel. New York State’s Regional Economic Development Council has awarded Vassar College a grant of over $1.2 million to “modernize their steam boilers and convert them to burn renewable fuel oil (RFO), reducing their usage of natural gas and lowering their carbon footprint.” The project, which falls under the auspices of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, has an anticipated completion date of April 1, 2024.

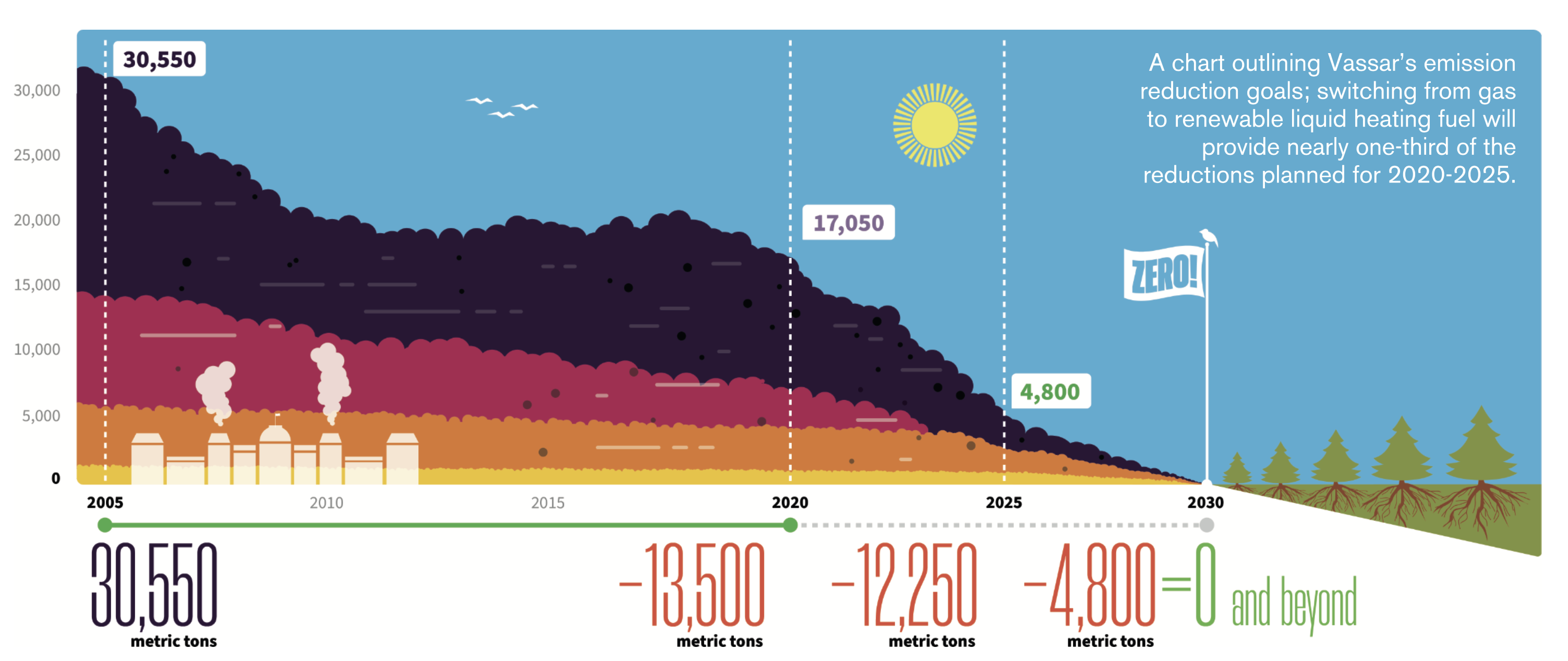

Founded in 1861, Vassar College is a private liberal arts school located in Poughkeepsie, New York. In 2020, the college adopted a Climate Action Plan (CAP) to become carbon neutral by 2030. The CAP includes a near-term decarbonization plan that the school describes as “immediately actionable” and “cost-effective,” laying the foundation for future greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions.

“Under this near-term plan, Vassar will convert two central boilers from natural gas as a feedstock to biofuel, for a 4,000 ton per year reduction in greenhouse gas emissions,” the CAP states. That’s equal to the annual emissions from 10 million passenger vehicle miles or 9,261 barrels of oil. Vassar intends to lower its GHG emissions from 2020 levels of 17,050 metric tons per year to just 4,800 metric tons by 2025, a reduction of 12,250 metric tons in just five years.

The heating system conversion will account for about one-third of this reduction.

That huge slice of the pie is a testament to the immediate and significant emission reductions provided by bio-based renewable liquid heating fuels, says Kris DeLair, executive director of the Empire State Energy Association.

Several companies in the region produce and sell renewable liquid heating fuels made from biodiesel, another kind of advanced biofuel, which is often blended with heating oil. Vassar says its biofuel will be “derived from sawdust and tree trimmings from commercial timber operations.” This cellulosic biofuel is branded RFO by Ensyn Technologies, a company from Quebec with plans to expand into New York.

“Instead of leaving these byproducts to release their embedded carbon through decomposition, the RFO process is able to convert the byproducts into an alternative to fossil fuels,” Vassar states. “While these still emit carbon dioxide through combustion, the net carbon footprint is considered significantly lower than alternatives like natural gas.”

From Fuel Oil to Gas and Back

Before 2005, petroleum-based fuel oil was used to heat numerous buildings across Vassar College’s 1,000-acre campus. The college then converted these buildings to natural gas heat, which emitted less carbon than petroleum, but did not get Vassar off of fossil fuels. Additionally, the climate benefits of methane-based natural gas have come under intense scrutiny over the past decades, as scientists have shown that methane emissions have even greater global warming impacts than carbon dioxide.

There have also been complaints about uneven heating. Faculty, staff and administrators cited in the CAP described “ancient heating systems that blast hot air into the winter night from the dorms, where windows have to be opened to cool down the room.” Vassar considered several options for heating system replacements, including electric heat pumps. The decision to switch to renewable liquid heating fuel for its immediate, cost-effective environmental benefits was driven in part by a report titled “A Future Heating Plan for Vassar College,” by Benjamin Shaffer of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Shaffer found that, in addition to providing significant GHG savings, renewable liquid heating fuel presented a “highly affordable” option. While transitioning the school’s central heating plant would cost approximately $1 million, “the fuel savings over five years would have a net present value of $1.37 million.”

By contrast, a proposed project to transition several buildings on Vassar’s campus from natural gas to electric heat pumps would also carry a price tag of about $1 million, but “heat pumps are not likely to save Vassar money in these buildings,” Shaffer wrote. Other heating upgrades considered in this plan include radiator covers and a solar hybrid system. Of all these projects, the renewable liquid heating fuel conversion provides by far the greatest annual cost savings and GHG reductions.

Precedents for Success

Bates College began adopting RFO with the help of Ensyn Technologies in 2017. That year, the school, located in Lewiston, Maine, converted one of its heating plant’s three boilers from natural gas to RFO. In 2019, a second RFO boiler was added. The equipment was fabricated by Preferred Utilities Manufacturing of Danbury, Connecticut and installed by Port City Mechanical of Portland, Maine. Together, the two boilers help heat buildings across all of Bates’ 1.1 million-square-foot campus.

According to an estimate from Bates College Sustainability Manger Tom Twist, the conversions reduced the school’s emissions by 95 percent compared with their 2001 baseline, putting the college “right on the cusp of carbon neutrality.” While transporting RFO to Bates from Ensyn’s refinery in Renfrew, Ontario produces about 134 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions per year, burning RFO instead of natural gas reduces the school’s emissions by 3,000 metric tons of CO2e annually.

Production and blending of cellulosic biofuels such as RFO generates D7 Renewable Identification Number (RIN) credits that petroleum refiners can purchase to meet their compliance obligations under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). This creates financial incentives not only for the producer and blender, but also the distributor and end user, as the RIN price can be factored into and subtracted from the fuel cost.

NEFI addressed some of the economic and environmental benefits of cellulosic biofuels in a comments letter sent to the United States Department of Agriculture earlier this year. “NEFI is excited about potential cellulosic fuels being developed for residential and commercial heating applications,” wrote NEFI President & CEO Sean Cota. “One such fuel, ethyl levulinate (EL), is a net-negative heating fuel that can be produced from sustainably harvested forestry products and cellulosic waste.”

Oil & Energy readers may recall reading about EL in articles from our August 2019 and November/December 2020 issues; as reported earlier, fuel wholesaler Sprague Resources LP and cellulosic biofuel producer Biofine Developments Northeast Inc. have signed a purchase agreement for the production and marketing of EL.

“Maine, which has the largest share of heating oil use per capita of any state, considers EL not only a viable alternative for space heating – but also for forestry management and rural development,” Cota stated in NEFI’s comments letter. “EL can be produced from slash and thinning, thereby helping to eliminate the risk of wildfires. There are an estimated 16 million tons of sustainably harvested feedstock available each year in the state. EL can utilize existing supply chains including local and sustainable logging and forestry industries and waste management operations. This could preserve an estimated 20,000 jobs and create thousands more throughout the state with the establishment of a new industrial biorefining industry.”

At press time in late June, Maine’s state legislature was considering a bill that could provide $40 million to help commercialize EL and other locally produced cellulosic biofuels. If approved, the bill would send a referendum to voters in November, asking them, “Do you favor a $40,000,000 bond issue to provide funds for investment in infrastructure supporting Maine’s forestry and natural resource industries through commercial development of environmentally sustainable and low-carbon fuels?”

“The Maine Energy Marketers Association [MEMA] is proud to support Senate President Troy Jackson’s bill, L.D. 1637, and urges the Legislature to send this measure to Maine voters,” said MEMA Vice President Megan Diver.

“EL is the right liquid fuel at the right time for Maine and, ultimately, the Nation,” she added.