Veteran meteorologist scans summer developments for winter signals

By John Bagioni, Fax Alert Weather Service

Ever since late winter (February into March period) the talk amongst many meteorologists, especially those who delve into the realm of long range forecasting, has been centered on the likelihood of an El Niño developing across the Pacific basin this summer.

As with all El Niño events, there are questions about how intense (warm) the event will be, where the warmest water will be centered, and lastly, whether there will be other ocean-based anomalies that might magnify or lessen some of the classic El Niño impacts across the Northern Hemisphere.

First, a little El Niño primer to bring everyone up to speed… El Niño is best defined by a long duration warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures when compared to normal. To be designated an official El Niño, many scientist look for a warming of about 0.5 degrees Celsius averaged over about a 3-month period across mainly the central and eastern equatorial Pacific. The global atmosphere may start exhibiting El Niño characteristics long before an official classification has been made. The length or staying power of an El Niño event can vary from a few months, usually more than six, to as long as five years in the extreme.

Results Vary

Historically during El Niño events we see rises in the average surface pressure over parts of the Indian Ocean, Indonesia and Australia. Pressures usually drop across Tahiti and much of the central and eastern Pacific equatorial zones. On average, areas of the western Pacific can see significant rainfall deficits, while areas adjacent to the eastern Pacific often see an increase in precipitation.

As for the impacts on the continental U.S., it can vary wildly from El Niño to El Niño, given the ability of other atmosphere controllers across the North Pacific and the Atlantic Ocean to assert enough influence on the El Niño to greatly modify what might be considered “normal” influences on the U.S. and Canada.

More about the expected climate impacts across the North American sector from this El Niño later in the article, but let’s take a look at the current and projected El Niño trends across the equatorial Pacific.

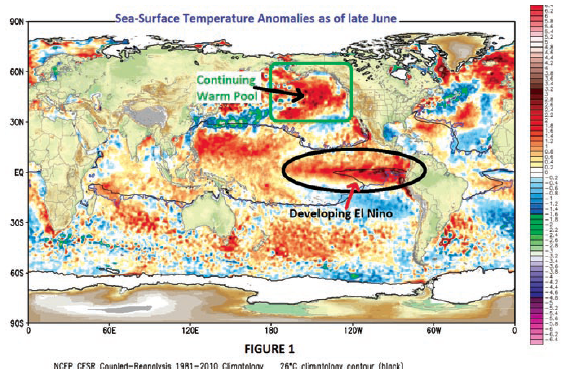

Figure 1 shows the global sea surface temperature anomalies (courtesy of WxBell.com) as of late June when this article was written. Note the black oval showing the tongue of very warm water emanating for the coast of northwest South America westward toward the central Pacific. This is the developing El Niño and for all purposes it has evolved at this point to what appears to be a full El Niño status. But given that it had not reached the time requirement (0.5 C averaged over 3 months) it was not yet classified as an “official” El Niño. But nonetheless the signature is very apparent.

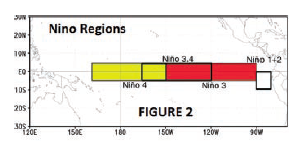

One of the things we watch for when trying to clarify how a particular El Niño event might impact the North American sector during the fall and winter seasons is where is the core of the warming, relative to the equatorial Pacific. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of El Niño regions. During late June and early July, the El Niño was clearly centered in Region 1-2 (far eastern Pacific).

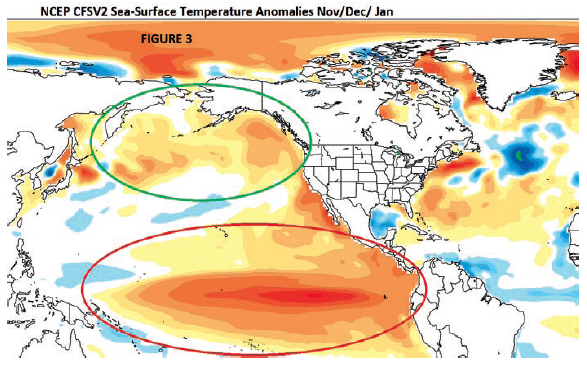

Figure 3 (also courtesy of WxBell.com) shows how the American modeling system is expecting the El Niño to evolve as we move into the late fall and winter period (November on through December). You can see a definite westward shift from Region 1-2 into Region 3.4. This means the core of the warmest water is expected to migrate westward as we move from the late summer period on into the fall and winter months.

Go West, El Niño

The change in where the core of the warmest anomaly exists can play a huge role in the wintertime impacts across the U.S. during El Niño events. Events that are east-centered (Region 1-2) can produce widespread warmer than normal conditions across the continental U.S. In fact, strong El Niño events that are eastern based have in the past produced some very mild winter across the eastern U.S., and while heavier than normal precip may fall from the West Coast on across the southern U.S. and up the East Coast, frequent snowstorms are not likely and many winter lovers are quite disappointed.

So for those of you wanting and hoping for a repeat of last year’s winter widespread colder than normal conditions you want to see the El Niño core shift steadily westward in the coming months. Central and western-based El Niño events hold the most promise for colder than normal wintertime conditions across the central and eastern U.S.

Back in the early stages of the El Niño discussions this spring there were some silly opinions calling for this to ramp up to Super El Niño status. In my opinion, there was never any support in the large-scale global pattern and/or current climate trends for a super strong event. In fact, evidence has continued to mount that this event will be moderate at best and will not be the beginning of a multi-year El Niño cycle.

Super, basin-wide El Niño can be completely overwhelming to other atmospheric controllers, and when they occur it is usually safe to play the classic El Niño impacts, including a call for widespread warmth during the winter season. Other more northern latitude ocean anomalies and their accompanying atmospheric features become very minor players during strong El Niño events. I do not expect that to be the case this year.

What Lies Ahead

So where does this leave us with respect to this El Niño? As Figure 3 indicates, I think we are on track to see the 2014-15 El Niño to become centrally located in Region 3.4, and I expect it to peak at moderate or lower strength.

Given that it will be no stronger than moderate and also centered in the 3.4 Region, I look for other ocean anomalies and atmospheric players to contribute significantly to the winter pattern. Of note, is the ongoing warm pool that has been situated across the North Pacific Ocean (near and south of Alaska) since last winter. I have highlighted this warm pool on both Figure 1 and Figure 3.

It is believed that the warm pool across the North Pacific last winter was the main reason we saw frequent, strong arctic intrusions build across northwest portions of Canada and then drop southeastward into the Central and Northeastern portions of the country. This warm pool allowed an upper level ridge to be an almost permanent jet stream feature north of Alaska on into western Canada. An upper level ridge in this position is very favorable for the delivery of arctic air into the lower-48, especially central and eastern portions of the country.

As you will see by comparing Figure 1 to Figure 2, the footprint of the North Pacific pool continues into the winter season. I like the chances of it staying around, on average, well into or through the winter season. This means that while some of the historic El Niño impacts would suggest warmer than normal conditions are more likely than cold conditions this winter, the presence of the North Pacific warm pool along with the fact that the El Niño will be only weak to moderate in intensity, suggest to me that the potential for the delivery of arctic air into southern Canada and the central and eastern U.S. will be greater than normal.

Ridging Alters Artic Intrusions

Small changes in the location and strength of any western Canadian ridging (caused by the North Pacific warm pool) will make for significant differences as to how strong and where the arctic intrusions go. But, in general, I like the fact that the footprint of the North Pacific warm pool remains in place.

The North Atlantic wild card (North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)) may play a bigger role this winter than last. Last winter saw a neutral to positive NAO, which usually favors eastern mildness. But the North Pacific signal overpowered the North Atlantic and cold air dominated the pattern. The North Atlantic Ocean anomaly pattern right now has a look of one more favorable (cold anomaly in central Atlantic/warmer northward around Greenland) for a –NAO. The negative phase of the NAO is more supportive of cold across the eastern U.S. If (big if), we can keep the North Pacific warm pool in play and get a modest –NAO to develop, cold air delivery will not be an issue this winter, even with a moderate El Niño in place.

It is also noted that solid El Niño events like the one developing usually provide an above normal precipitation pattern from the West Coast on across the Southern U.S. and up the East Coast. I will assume that will be the case again with this El Niño event, and given the signal for frequent cold intrusions, it could be a pretty big snow season from the Southern Appalachians northward through the Middle Atlantic, New York and New England regions.

As for hurricane activity, most El Niño events lead to fewer than average tropical storm or hurricane numbers. But that does not mean an inactive or easy season. There is evidence to believe that while hurricane development across the southern tropical Atlantic will be less than normal, significant activity may be concentrated from just east of Florida northward into the Carolinas and points north into New England. So while the numbers may be down, all it takes is one ill-timed storm to cause major problems and the East Coast should be wary of becoming complacent.