All

High-Efficiency Oilheat Equipment vs. Electric Heat Pumps

An energy cost comparison supported by field studies and laboratory analysis

Today’s electric heat pumps do not provide energy cost savings over high-efficiency oil-fired heating systems. Field studies demonstrate and laboratory analyses confirm that high-efficiency hydronic heating systems almost always cost less to run than electric heat pumps. The only exceptions are theoretical models, i.e., heat pumps performing at levels not yet observed in the field.

This is based on industry discussions of a recent study by the National Oilheat Research Alliance (NORA), which analyzed New York homes utilizing both hydronic boilers and ductless, air-source heat pumps. Importantly, the study — commissioned by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) — did not set out to determine which kind of heating system is cheapest to run, but instead to develop “Best Practices” for using both kinds in a hybrid mode (as this was NYSERDA’s aim).

The general conclusions of that study were covered in the August 2021 issue of Oil & Energy (see “NORA Releases Heat Pumps Controls Strategy Guide,” page 40, print edition), and the full report is available online at noraweb.org (under “Heat Pump Project Report”). This article draws from that study as well as discussions of it that took place September 14 at the 2021 HEAT Show as NORA Laboratory Director Tom Butcher presented “What’s the Biggest Bang for the Buck: High Efficiency Oilheat Equipment or Electric Heat Pumps?”

Hybrid Heating Costs By the Numbers

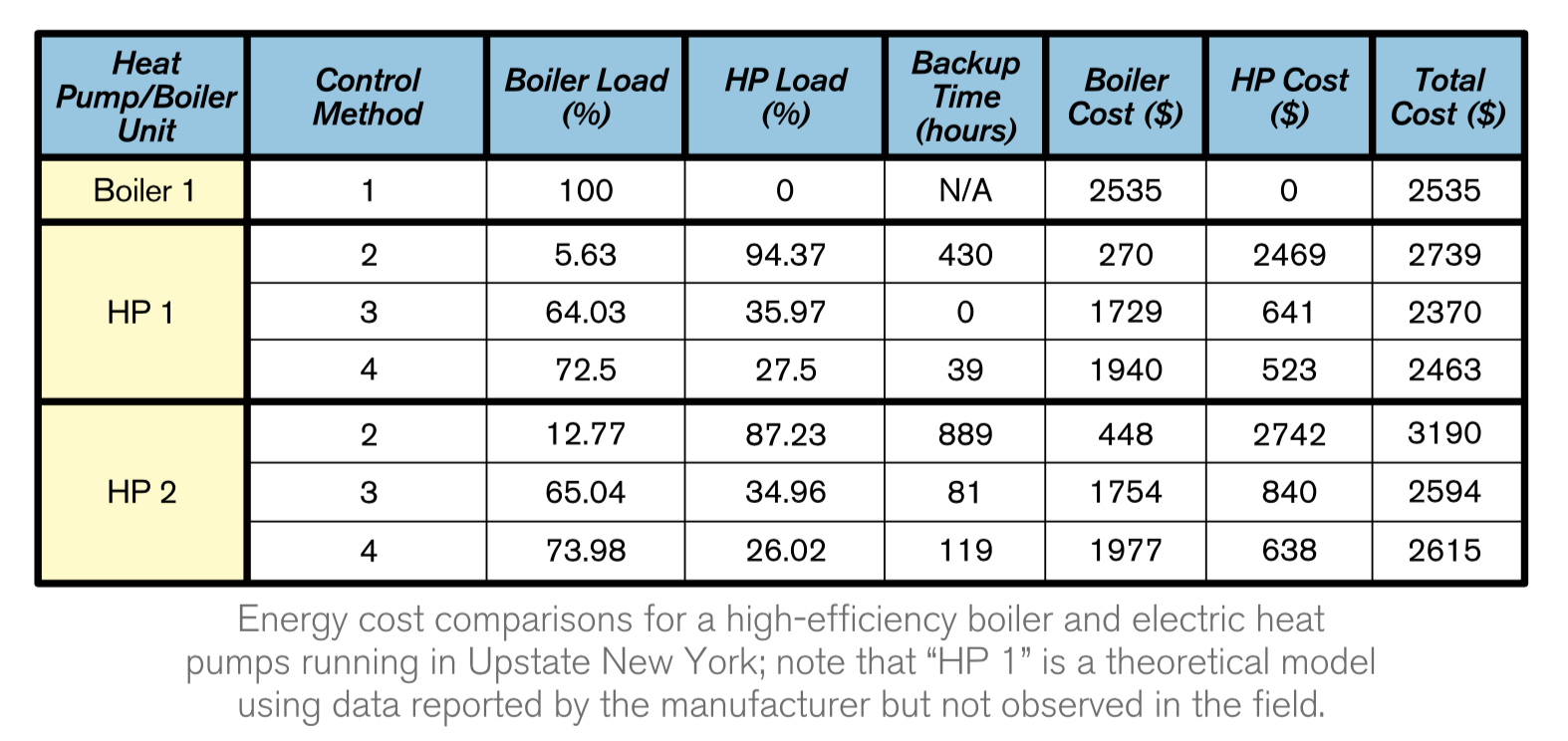

The NORA study analyzed “hybrid” heating systems (those using both boilers and heat pumps) at six residential locations in New York State — three homes on Long Island, one in the Hudson Valley, and two in Upstate New York.

Because the Department of Energy standard boiler efficiency rating AFUE does not account for domestic hot water integration, NORA applied an alternate calculation of steady state thermal efficiency as a percentage of system output measured by Btu/hour. Heat pump performance curves were based on manufacturer specific Coefficient of Performance (COP) ratings and reported field studies of actual performance.

Additionally, four switchover control methods were used: 1) boiler only; 2) heat pump operates as primary source, boiler provides heat only when heat pump cannot meet load; 3) heat pump operates when outdoor temperature is over 25°F, boiler operates at 25°F or colder; 4) heat pump operates from March 1 to November 1, boiler operates for the rest of the year.

According to data Dr. Butcher presented at the HEAT Show, using only a high-efficiency boiler provided annual cost savings of as much as $655. These highest savings were in comparison to a home in Upstate New York using control method 2. Energy costs varied by location, boiler and heat pump type, and control method, but in general, using only a high-efficiency boiler provided lower residential heating costs in most cases.

One notable exception was lab-modeled “Heat Pump 1,” whose theoretical Coefficient of Performance (COP) might allow for cost savings in certain locations. However, as the study notes, “values for heat pump 1 are not verified by field data but are rather manufacturer reported.” Indeed, the study states that this model was included “to reflect discrepancies between theoretical and field data.”

Another exception was lower-efficiency tankless coil boiler models, which demonstrated very high idle loss and low steady state efficiency, especially during summertime water heating operations. Improvements in these areas may be a main priority for boiler manufacturers in the years to come (more on boiler efficiency in the final section of this article).

It is worth noting here that the study assumed energy costs of $2.39 per gallon for heating oil and 19.1 cents per kilowatt hour for electricity – significantly lower than the current prices of heating oil and electricity, as the study took place in the winter of 2018-2019. Asked about this discrepancy during the presentation, Dr. Butcher replied that changes in fuel prices always occur and we don’t really know how they will change in the future.

Dr. Butcher added that if the entire building sector were to be electrified, the demand for and price of heating oil might be reduced while the price of electricity might be higher. (For further discussion of electricity price spikes under proposed electrification initiatives, see “Loose Screw Economics” from the November/December 2019 issue).

Cost Was Not the Deciding Factor

While the NORA study considered different “strategies” for using a combination of boilers and heat pumps, it would be a stretch to classify the studied households’ decisions to use one system over the other at any given moment as strategic.

On the contrary, most of the homeowners in the study never consciously turned off their boiler and turned on their heat pump, or vice versa, unless they were using a heat pump to provide added warmth in one particular zone of the house. Furthermore, several homes tended to use a boiler and heat pump simultaneously on the coldest days of the year, even though the heat pump’s efficiency and heating capacity would be reduced at these times.

All of this speaks to the fact that cost was not the biggest influencer in determining heating system usage, as observed in the study. During the presentation, Dr. Butcher suggested that keeping a particular room, such as a home office, at a specific temperature throughout the day could be an ideal application for a mini-split heat pump. Beyond that, however, it would be difficult to apply any kind of logic, let alone strategy, to the usage patterns observed in most of the homes included in the study.

If there was any deciding factor in determining whether or when homeowners actually used their boilers or heat pumps, it was their own personal behavior motivated primarily by a desire for greater comfort. As for the act of manually switching over from one system to the other, “People didn’t think about it,” Dr. Butcher said.

In response to this observation, one industry stakeholder in attendance at the presentation admitted that his office was located in a building with a number of heat pumps that had been installed “to provide zoning flexibility.” However, in just about every place with a heat pump, “there’s also an electric heater on the floor,” he said, as the wall-mounted heat pumps failed to provide even temperatures throughout the offices.

Drawing from this experience, the attendee suggested that those building owners whose motivation to install electric heat pumps is political in nature may not understand “the distinction between space heating and central heating,” never mind the intricacies of efficiency and cost comparisons between different energy sources and heating systems.

True, but this also provides further opportunity for consumer education. And a second NORA study, discussed later in the presentation, provides some additional food for thought by showing how much high-efficiency oil-fired heating systems can help homeowners reduce their fuel consumption.

Upgrading Savings

While there may not be much financial incentive for homeowners to use their existing heat pumps instead of their oil-fired heating system, a compelling case can be made for upgrading to a higher-efficiency boiler or furnace. To calculate how much fuel and money can be saved, NORA lab intern Michael Persch — an engineering student at Stony Brook University — took a closer look at NORA’s rebate program.

In most cases, the database for NORA rebate programs includes the make, model, age, and estimated AFUE of the old heating system, as well as the make, model and estimated AFUE of the new unit. However, as Dr. Butcher pointed out, this alone is not enough to make a definitive determination on fuel consumption reductions and energy cost savings. To cross that bridge, Persch analyzed delivery and degree day data obtained from five service companies that perform heating system upgrades under a NORA rebate program.

After using delivery data to generate a fuel consumption curve, putting old and new heating systems into six different categories with different steady state efficiency and idle loss for each, and calculating estimated savings based on these categories, Persch compared these predictions with actual reductions in consumption based off the delivery data. He then weighted these findings based on the amount of different kinds of heating system upgrades performed across 112 sites. His findings were previewed during the HEAT Show presentation and are expected to be released in full as an upcoming report.

Based on these findings, upgrading to a higher-efficiency oil-fired heating system reduces the average home’s fuel consumption by 136 gallons per year, or 16%. This reduces the average homeowner’s fuel costs by $420 per year, based on a heating oil cost of $3.10 per gallon.

According to a database maintained by New York-based marketing firm PriMedia, Inc., as of November 11, 2021, 8,625 boiler and furnace upgrades had been performed under NORA-sponsored Upgrade & Save rebate programs since 2015. If each of these upgrades reduces heating oil usage by 136 gallons per year, then this has lowered U.S. homeowners’ annual fuel consumption by more than 1.1 million gallons.

In other words, not only are high-efficiency oil-fired heating systems much more affordable and cheaper to use than electric heat pumps — they’re also arguably doing a better job of fulfilling heat pumps’ supposed purpose, eliminating fossil fuel consumption.

Related Posts

From Blue Flame to Biofuels

From Blue Flame to Biofuels

Posted on June 25, 2025

HEAT Show Announces Fenway Park Backyard BBQ

HEAT Show Announces Fenway Park Backyard BBQ

Posted on May 15, 2025

Delivering New York City’s Clean Energy Solutions

Delivering New York City’s Clean Energy Solutions

Posted on May 14, 2025

Are You a Leader or a Boss? The Choice is Yours

Are You a Leader or a Boss? The Choice is Yours

Posted on May 14, 2025

Enter your email to receive important news and article updates.