EPA’s new emissions regulations step away from reality

New regulations from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for heavy duty trucks set emission reduction requirements through model year (MY) 2032, expanding the “Phase 2” emissions rule issued in 2016. These new rules, released in late March, came on the heels of the Emissions Standards for “light-duty and medium-duty vehicles” issued about a week earlier.

The new standards apply to heavy-duty vocational vehicles, such as delivery trucks, refuse haulers, public utility trucks, transit, shuttle, and school buses, and tractors, including day cabs and sleeper cabs on tractor-trailer trucks. The “Light-Duty and Medium-Duty Vehicles” standards include passenger cars and light trucks. In other words, they apply to service vans and delivery trucks that are the backbone of the liquid heating fuels industry!

While purportedly “technology neutral,” there is little doubt that the aim is to transition the country from internal combustions engines (ICE vehicles or ICEV) to Zero Emissions Vehicles (ZEVs). There are, however, several glaring problems in their calculations.

“Once again, the so-called experts have set standards with no basis in reality. By excluding real-life factors like range, tonnage and reduced air emissions from biofuels, the EPA has developed a set of standards that are destined to fail. The unspoken goal of the EPA and the Administration is to drive up the costs of conventional liquid fuel equipment so that electric trucks don’t look as ridiculous as they do now. It will increase costs, reduce operational efficiency, delay life-saving deliveries to homeowners, keep older trucks on the road, and increase GHG emissions because of fossil-fuel derived electricity,” said Sean Cota, President of the National Energy & Fuels Institute.

Light- and Medium-Duty Vehicles

The new standards for the smaller vehicles scale back previous proposals for the first few years, but ramp up to require that 60 percent of new vehicles are electrified – or otherwise reach the emissions standards – by 2032.

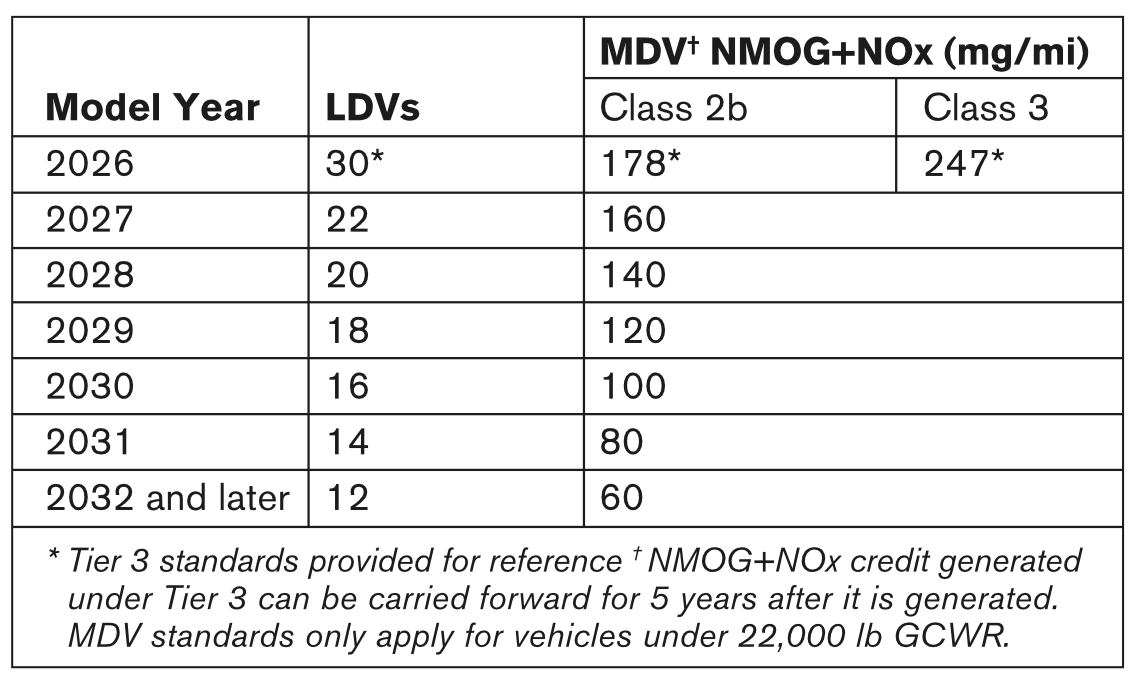

For light-duty vehicles (LDVs), EPA is proposing non-methane organic gases (NMOG) plus nitrogen oxides (NOx) standards that would phase-down to a fleet average level of 12 mg/mi by MY 2032, representing a 60 percent reduction from the existing 30 mg/mi standards for MY 2025 established in the Tier 3 rule in 2014. For medium duty vehicles (MDVs), EPA is proposing NMOG+NOx standards that would require a fleet average level of 60 mg/mi by MY 2032, representing a 66 percent to 76 percent reduction from the Tier 3 standards of 178 mg/mi for 2b vehicles and 247 mg/mi for class 3 vehicles. EPA is proposing cold temperature (-7°C) NMOG+NOx standards for light and medium-duty vehicles to ensure robust emissions control over a broad range of operating conditions. The proposed standards would also reduce emissions of mobile source air toxics. Once phased into the Tier 4 program, vehicles would be required to meet the proposed fleet average standards shown at right.

According to the EPA, cost is “not” going to be a factor, despite their estimates of up to $1,200 per vehicle in technology costs for the automakers. The unknown increase to the retail price, according to the EPA, will be offset by Inflation Reduction Act incentives of up to $7,500 for an electric vehicle plus long-term savings on repairs and maintenance and fuel vs. electricity costs.

Heavy-Duty Vehicles

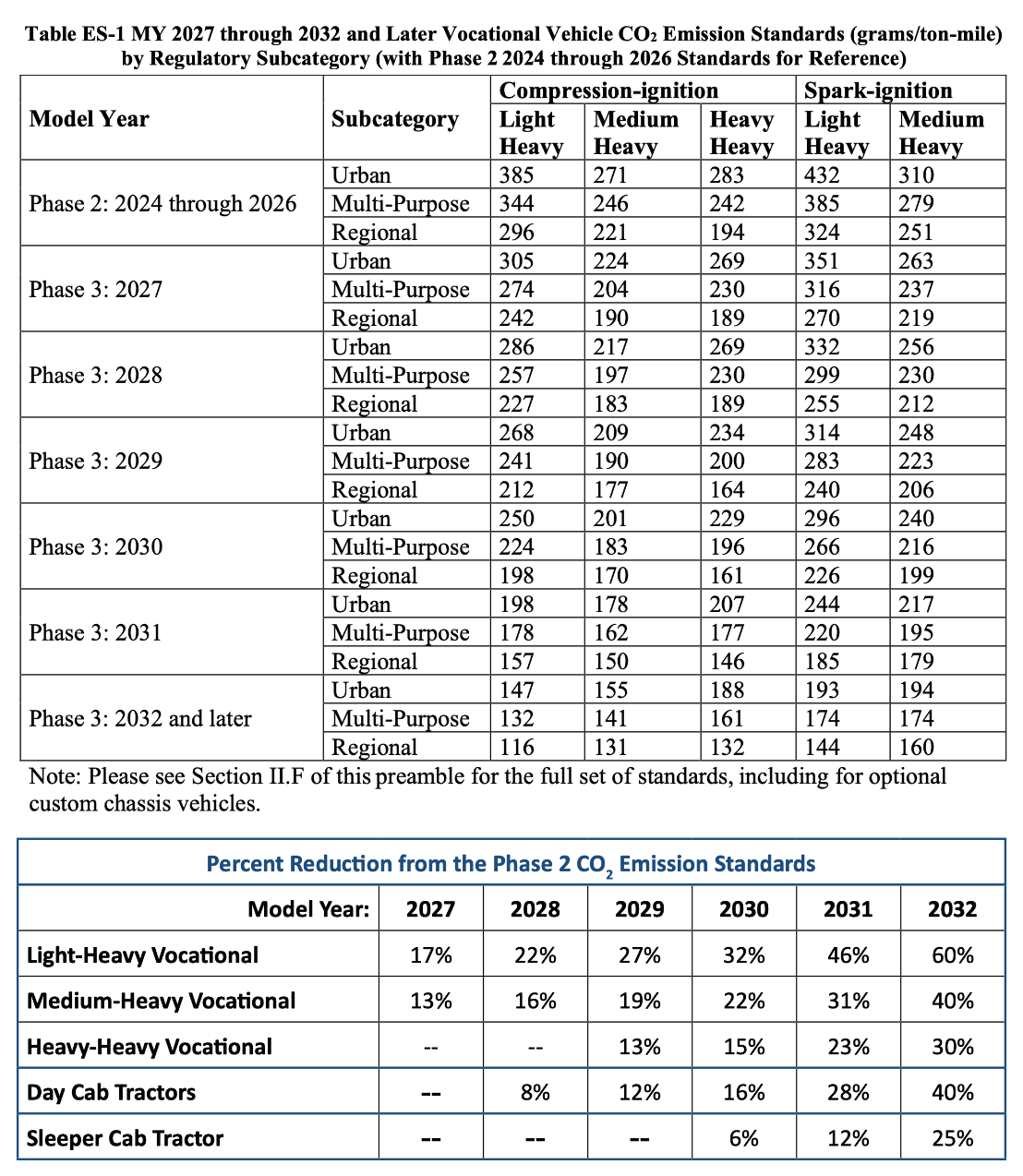

The Phase 3 standards released last month for heavy-duty vocational vehicles expand upon the Phase 2 standards issued in 2016. The EPA categorized vehicles into weight classes based on gross vehicle weight ratings (GVWR). These weight classes span Class 2b pickup trucks and vans from 8,500 to 10,000 pounds GVWR through Class 8 line-haul tractors and other commercial vehicles that exceed 33,000 pounds GVWR.

Phase 3 revised MY 2027 standards from Phase 2 and set lower than anticipated standards for MY2028 based on feedback during the comment period.

“After further consideration of the lead times necessary to support both the vehicle technologies’ development and deployment and the infrastructure needed, as applicable, under the potential compliance pathway’s technology packages described in Section ES.C.2.iii, EPA is finalizing GHG emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles that, compared to the proposed standards, include less stringent standards for all vehicle categories in MYs 2027, 2028, 2029 and 2030. The final standards increase in stringency at a slower pace through MYs 2027 to 2030 compared to the proposal,” the report states.

By 2032, 30 percent of heavy-heavy duty vocational trucks would need to be zero-emission, and 40 percent of regional day cabs. Despite EPA’s “technology neutral” claims, and taking into consideration that exhaust pipe emissions are the only metric considered, it will be difficult to reach the annual benchmarks with integrating hybrid, battery-electric, or hydrogen-electric trucks.

What it All Means to Liquid Heating Fuels Dealers

There has been a lot of talk about how these new standards will affect long-haul trucking – the companies and drivers who travel the Interstates across the country. Often lost in the conversation are the local drivers, like those delivering heating oil and propane. Many of these vehicles are built to carry 2,700 gallons of heating oil or 3,400 of propane, keeping them within the “federal bridge formula” of a max 22,400 lbs per axle and, as importantly, keeping their GVWR under the 33,000 lb Federal Excise Tax (FET) threshold, according to Mike Trask, Owner and President of Hall-Trask Equipment. With the average truck costing approximately $200,000, and many much higher, the 12 percent FET is a huge incentive to keep the weight under the limit.

Hall-Trask turns basic vehicles into custom fuel trucks. It’s Trask and his team who mount the equipment and connections, and build the tank to the chassis weight. “Every time they add these regulations, they add weight and take away space, and put inherent operation limitations on the truck,” Trask said. Trask looks at one specific emissions regulation, limiting idling time for trucks. As most readers will know, in the liquid heating fuels market, idling time is often the most profitable time for delivery trucks, because the pumps only work while the truck is idling. With the average truck making 25-30 deliveries a day, the truck could be operating at idle for as much as 65 percent of its time. New trucks, in order to meet idling standards, are built with automatic engine shutdowns that must then be disconnected so a fuel truck does not shut off in the middle of a delivery. “These standards may be good for long haul or box trucks, but not our system. The average fuel company is looking to minimize miles and maximize deliveries. That is the complete opposite of what a lot of these standards are made for,” Trask says.

Trask is pragmatic about fleet electrification, adding, “Electrification is something we have to deal with, and but it needs to be practiced in moderation.” At the same time, his expertise in building fuel trucks puts the future of battery electric vehicles in doubt.

While there aren’t specific weights available for not-yet-available batteries for fuel oil or propane tankers, Trask considers the FET and federal bridge limits as he looks to the future. The 2,700 gallon tank keeps fuel trucks below the 22,400 lbs per axle bridge maximum. Electrification is expected to reduce the payload in tractor trailers by up to 30 percent. If that holds for oil trucks, their 2,700 gallons will be cut to less than 1,900. At that capacity, they will be making only 10-15 deliveries a day and requiring more frequent trips to the terminal.

“That’s a big problem. If we lose 30 percent of our load, we’ll lose 30 percent of productivity. That affects the bottom line, increases the price of fuel because the cost of delivery goes up substantially,” he concludes.

As a company that builds gasoline trucks as well as heating oil and propane, Trask sees another issue with battery electric or hydrogen fuel cell electric trucks. “I don’t want to put the fear of God into people. We’ll build a responsible truck, one that’s safe. But they need to think about what could go wrong, putting a potential ignition source on top of batteries!”

At the same time, Trask is optimistic. “The industry is strong and resilient. Customers are reinvesting in their businesses. We’ll be ready for whatever comes. We are pushing forward with success, any way we can produce a better product,” he says.

Other Voices, Similar Sentiments

Leaders of the trucking and fuel industries quickly voiced their opinions once the EPA Heavy-Duty Truck Emissions Rule was released.

“EPA’s rule flatly dismisses the benefits of biodiesel and renewable diesel as the lowest-cost and most widely available options to kickstart decarbonization of the heavy-duty vehicle sector,” said Kurt Kovarik, Vice President of Federal Affairs with Clean Fuels. “There should be no uncertainty that biodiesel and renewable diesel also reduce criteria pollutants from heavy-duty vehicles, which will continue to be manufactured and used during the timeframe of this rule. EPA should recognize that biodiesel and renewable diesel merit a role in meeting these emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles.”

Clean Freight Coalition Executive Director Jim Mullen issued a statement in which he said, “The GHG Phase 3 rule will have detrimental ramifications to the commercial vehicle industry, many small and large businesses, commercial vehicle dealers and their customers. A recent study contracted by the CFC demonstrated that fully electrifying the nation’s medium- and heavy-duty commercial vehicles will cost motor carriers $620 billion in charging infrastructure alone. That does not include the vehicle cost which increases by 2-3 times compared to a diesel truck – costs that will ultimately be borne on the backs of consumers.”

“Comparable electric trucks cost two-to-three times more than the current fleet that carries 73 percent of the nation’s freight. That means the cost of almost three-quarters of the goods Americans buy will go up – for good. That is before the additional nearly $1 trillion in required infrastructure investment. Forcing adoption of more expensive vehicles that are not yet demanded by the market nor ready for prime time should be a lesson already learned, given the widespread failure of electric bus fleets and abrupt slowdown in passenger EV sales, despite billions of taxpayer dollars being spent,” Consumer Energy Alliance Vice President Kaitlin Hammons said.

In his blog on EnergyTechForum.org, Allen Schaeffer said, “Their ultimate success in achieving the new standards is entirely dependent on the development of new fueling and charging infrastructure for hydrogen and battery electric vehicles, as well as consumers’ willingness to purchase the new vehicles. Regrettably, neither EPA rule is based in life-cycle emissions analysis, but only tailpipe emissions. This approach fails to take into consideration the emissions and energy required to produce the fuels and energy storage systems. A life-cycle approach supports consumer choice for both fuels and vehicles.”

American Trucking Associations (ATA) President and CEO Chris Spear said, “Given the wide range of operations required of our industry to keep the economy running, a successful emission regulation must be technology neutral and cannot be one-size-fits-all. [Emissions targets remain] entirely unachievable given the current state of zero-emission technology, the lack of charging infrastructure and restrictions on the power grid. Any regulation that fails to account for the operational realities of trucking will set the industry and America’s supply chain up for failure.”

“Small business truckers, who happen to care about clean air for themselves and their kids as much as anyone, make up 96% of trucking. Yet this administration seems dead set on regulating every local mom and pop business out of existence with its flurry of unworkable environmental mandates. This administration appears more focused on placating extreme environmental activists who have never been inside a truck than the small business truckers who ensure that Americans have food in their grocery stores and clothes on their backs. If you bought it, a trucker brought it,” said Todd Spencer, President of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association.