Personal reflections on those proud Americans who’ve fought for our way of life

Learning about Vets 2 Techs — an organization formed to connect returning vets who are in need of jobs, with the heating oil and propane industry, which is in need of qualified, new employees — I couldn’t help but reflect on how our country has supported its troops over the years. This also gives me cause to share a story from my family’s history, which I hope might inspire readers to revisit their own.

Public sentiment relative to wars and warriors has ebbed and flowed over time. My generation was generally opposed to the Vietnam War. Many protested by burning draft cards, moving to Canada to avoid the draft, etc., but most just went on with their lives, continued their education and hoped for a high draft lottery number, as I did.

Public sentiment relative to wars and warriors has ebbed and flowed over time. My generation was generally opposed to the Vietnam War. Many protested by burning draft cards, moving to Canada to avoid the draft, etc., but most just went on with their lives, continued their education and hoped for a high draft lottery number, as I did.

After 9/11, however, public sentiment changed. The United States coalesced in a patriotic show of unity, and citizens once again returned to openly expressing their appreciation for those who serve our nation. It is a common sight to see someone thank a uniformed serviceman when he walks past. And it is not uncommon to see a businessman seated in first class offer his seat to a uniformed servicewoman boarding a flight.

When it comes to World War II and our Greatest Generation, as Tom Brokow has termed them, most all Americans strongly supported that war and the troops who fought it, most of whom volunteered, some even lying about their age to enlist. But the odd truth about those returning veterans is they never talked about their experiences.

Recently, my siblings and I have taken an interest in our late uncle, my namesake, Thomas John Tubman, a WWII B-17 pilot who was lost over Dresden. His brother, my dad, died 18 years ago. My mother has since remarried, and my brother, in striking up a relationship with mom’s new husband, has learned that he was a navigator on B-17s during WWII. Not only that, but on some missions he was the lead navigator of the lead plane. This would have made him a key member of the flight team, but he never mentioned his role until asked by my brother.

Recently, my siblings and I have taken an interest in our late uncle, my namesake, Thomas John Tubman, a WWII B-17 pilot who was lost over Dresden. His brother, my dad, died 18 years ago. My mother has since remarried, and my brother, in striking up a relationship with mom’s new husband, has learned that he was a navigator on B-17s during WWII. Not only that, but on some missions he was the lead navigator of the lead plane. This would have made him a key member of the flight team, but he never mentioned his role until asked by my brother.

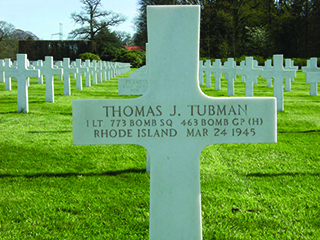

Likewise, there was very little mention of my uncle’s loss during my formative years. My grandmother was a Gold Star Mother who dressed the part and attended monthly meetings, but from what I remember, there wasn’t much talk of my uncle’s passing when I was growing up. The only reminder of his death came once a year when I was in grade school at Saint Brendan’s School. On the anniversary of my uncle’s death, March 24, 1945, my mother and father would have a Mass offered in his memory. When the notice was announced from the pulpit, calling out the name my uncle and I share, my fellow students would confusedly look around to see if I was still with them. Aside from that, there wasn’t much talk about my Uncle Tom and his ultimate sacrifice.

***

When my brother, my two sisters, and I first began researching the history of my uncle’s service and death, about seven or eight years ago, not much was readily available. However, in the last couple of years a wealth of information has surfaced. We learned the tail number of my uncle’s plane, found images of the “nose art” from the plane known as Betty Lou, learned the names of all its crewmembers, and read a declassified “missing crew report” with details about his mission on that fateful day in March 1945 (just a few months before the war’s end). And although none of my uncle’s crewmembers are still alive, we have been in touch with the families of three of them. We even learned about an organization created by the survivors of the 463rd Bomb Group (Heavy), of which my uncle’s 773rd Bomber Squadron was a part. My brother and one of my sisters have since joined.

When my brother, my two sisters, and I first began researching the history of my uncle’s service and death, about seven or eight years ago, not much was readily available. However, in the last couple of years a wealth of information has surfaced. We learned the tail number of my uncle’s plane, found images of the “nose art” from the plane known as Betty Lou, learned the names of all its crewmembers, and read a declassified “missing crew report” with details about his mission on that fateful day in March 1945 (just a few months before the war’s end). And although none of my uncle’s crewmembers are still alive, we have been in touch with the families of three of them. We even learned about an organization created by the survivors of the 463rd Bomb Group (Heavy), of which my uncle’s 773rd Bomber Squadron was a part. My brother and one of my sisters have since joined.

The B-17G had a crew of 10, and on March 24, 1945, they were on a mission to Berlin to bomb factories that were producing military armament. Flying from their base in Celone, Italy, they were joined by other heavy bombers in what was one of the largest bombardment missions of the war. And, without midair refueling capabilities, they were at the limit of their range. When they were hit by enemy aircraft fire, one crewmember was injured. First aid was administered to him, and he was parachuted out before my uncle ordered the other crewmembers to bail out as well. After the last crewmember jumped, the plane, with a wing on fire, exploded before my uncle could get out. The parachuted crewmembers landed behind enemy lines in Germany and were taken prisoner. Unfortunately, my uncle and the injured crewmember didn’t make it, but everyone else eventually came home.

The B-17G had a crew of 10, and on March 24, 1945, they were on a mission to Berlin to bomb factories that were producing military armament. Flying from their base in Celone, Italy, they were joined by other heavy bombers in what was one of the largest bombardment missions of the war. And, without midair refueling capabilities, they were at the limit of their range. When they were hit by enemy aircraft fire, one crewmember was injured. First aid was administered to him, and he was parachuted out before my uncle ordered the other crewmembers to bail out as well. After the last crewmember jumped, the plane, with a wing on fire, exploded before my uncle could get out. The parachuted crewmembers landed behind enemy lines in Germany and were taken prisoner. Unfortunately, my uncle and the injured crewmember didn’t make it, but everyone else eventually came home.

As we began to learn the details, we decided to plan a trip to my uncle’s grave in the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupré, Belgium, which we took together last month. But before I get to that, let me backtrack a bit…

As we began to learn the details, we decided to plan a trip to my uncle’s grave in the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupré, Belgium, which we took together last month. But before I get to that, let me backtrack a bit…

For the last several years, I have traveled with the National Association of Oil & Energy Service Professionals (OESP) to the ISH (and on alternate years, the Mosta Convigno) trade shows. Bob Chapman routinely travels with the group and is a bit of a WWII buff. He has led us on many side trips, including: Bastogne, Monte Cassino, Anzio, and other historical WWII sites. This March, he brought us to the Provence region of southeastern France. Among the many places we visited there was the Rhone American Cemetery in Draguignan, where Superintendent Andy Anderson provided us a guided tour of the site’s 861 graves. Andy had intimate knowledge of the soldiers buried there, including family history and even pictures of some of the fallen. Having already planned to visit my uncle’s grave, I reached out to the American Battle Monuments Commission in Washington, DC, to see if there was an Andy-type at the Ardennes American Cemetery, who might meet us upon our arrival. The commission responded promptly and forwarded our communication to the superintendent there, Mike Yasenchak.

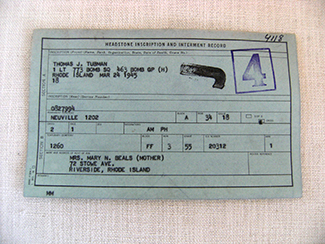

When we arrived, Mike greeted us and presented us with a “Next Of Kin” package including what information they had on our uncle, as well as some additional info on the cemetery and on the American Battle Monuments Commission, which maintains 26 of these cemeteries around the world. Following some conversation, Mike escorted us to our Uncle Tom’s grave. In the ground before the gravestone, Mike planted a small American flag. He then took from his backpack a container and opened it. He told us that the sand inside was from Omaha Beach in Normandy and explained that there were two reasons he had this beach sand with him: the first was that it was appropriate, since so many soldiers who were buried in American Battle Monuments Cemeteries in Europe entered the continent over Omaha Beach, and the second, he said, would be apparent in just a minute. With that, Mike proceeded to take a handful of sand and rub it over the inscription on the white marble tombstone, filling in the etchings of my uncle’s name and rank. He then took a dry sponge and carefully wiped away the excess sand on the surface surrounding the inscription. As a result, only the sand in the etched areas remained, highlighting the inscription in a kind of gold-leaf shimmer.

When we arrived, Mike greeted us and presented us with a “Next Of Kin” package including what information they had on our uncle, as well as some additional info on the cemetery and on the American Battle Monuments Commission, which maintains 26 of these cemeteries around the world. Following some conversation, Mike escorted us to our Uncle Tom’s grave. In the ground before the gravestone, Mike planted a small American flag. He then took from his backpack a container and opened it. He told us that the sand inside was from Omaha Beach in Normandy and explained that there were two reasons he had this beach sand with him: the first was that it was appropriate, since so many soldiers who were buried in American Battle Monuments Cemeteries in Europe entered the continent over Omaha Beach, and the second, he said, would be apparent in just a minute. With that, Mike proceeded to take a handful of sand and rub it over the inscription on the white marble tombstone, filling in the etchings of my uncle’s name and rank. He then took a dry sponge and carefully wiped away the excess sand on the surface surrounding the inscription. As a result, only the sand in the etched areas remained, highlighting the inscription in a kind of gold-leaf shimmer.

To characterize the experience as “very emotional” would be an understatement. We were overwhelmed by the reception we received and everything that followed. I should also note how we saw evidence of ongoing efforts to identify the Unknown Soldiers buried there. I’d first learned about this work from Andy during my visit to the cemetery in Provence. During my family’s visit to the cemetery in Ardennes, we saw preparation underway to exhume two identified servicemen, whom they now think can be identified. Out of respect and privacy, they only exhume bodies at night when the cemeteries are closed to the public. Using DNA samples provided by family members, they are identifying some of these Unknown Soldiers.

To characterize the experience as “very emotional” would be an understatement. We were overwhelmed by the reception we received and everything that followed. I should also note how we saw evidence of ongoing efforts to identify the Unknown Soldiers buried there. I’d first learned about this work from Andy during my visit to the cemetery in Provence. During my family’s visit to the cemetery in Ardennes, we saw preparation underway to exhume two identified servicemen, whom they now think can be identified. Out of respect and privacy, they only exhume bodies at night when the cemeteries are closed to the public. Using DNA samples provided by family members, they are identifying some of these Unknown Soldiers.

This was the fourth American Battle Monuments Cemetery that I have visited, and all the cemetery grounds are beautiful and impeccably kept. I would also add that the mission-dedication and respect for our fallen soldiers that I observed from Mike in the Ardennes and Andy in Provence was exceptional. All Americans should be proud of the way our country takes care of its fallen soldiers. It serves as a reminder that we should strive to show our respect, care and support for those soldiers who are still among us…

***

Which takes me back to the newly formed Vets 2 Techs initiative. Our servicemen and servicewomen sacrifice a lot for our country. And though today most Americans routinely thank them for their service, Vets 2 Techs provides a meaningful way for our industry to offer its appreciation and support. At the same time, Vets 2 Techs helps support the needs of our industry as well. The founders, Gerry Brien, Leo Verruso and Jesse Lord all deserve a big shout-out for creating this terrific outreach program.