With Low Carbon Fuel Standards, Clean Heat Standards and similar laws under consideration in most states, renewable fuels have gotten a lot of attention. One of these is renewable propane. Recently, renewable propane was lambasted in a news article published by The Guardian and Heated. But despite the smears in these publications, the facts are quite different.

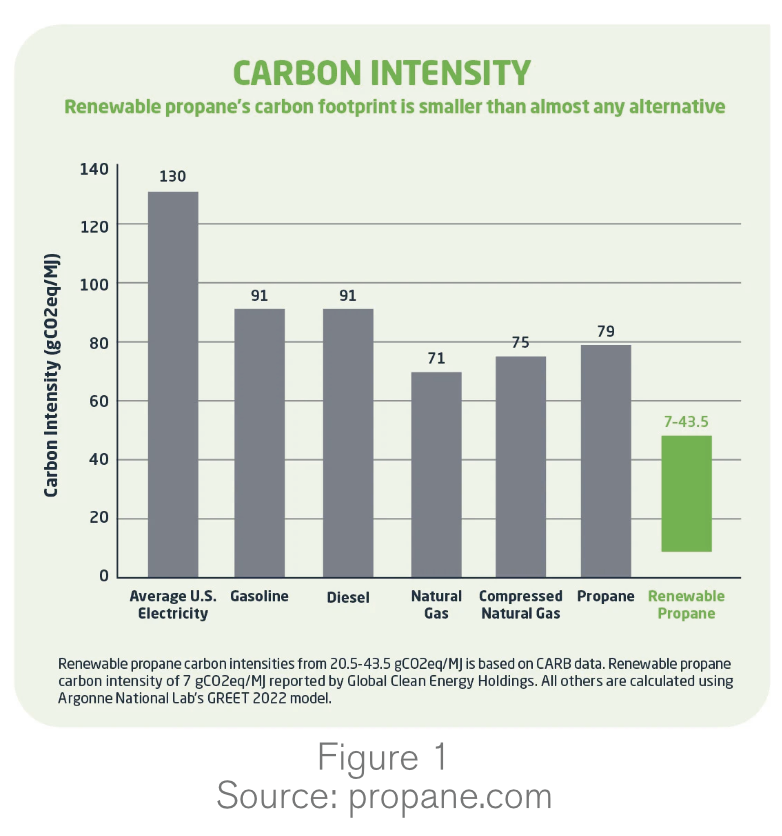

The Department of Energy recognizes renewable propane as a drop-in replacement fuel for all propane applications. As with biodiesel, renewable propane is produced from natural fats (tallow), vegetable oils, used cooking oils and other types of grease. As the Propane Education & Research Council (PERC) explains, biodiesel refineries can produce renewable propane from these fats and oils before they are used to produce biodiesel, giving materials once resigned to the landfill a new life. PERC’s research has determined that renewable propane has an ultra-low carbon intensity, less than most other energy sources (see Figure 1).

At present, renewable propane is mostly produced and utilized on the West Coast to meet the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard and the Clean Fuel Standards in Washington and Oregon. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) calculates a carbon intensity (CI) score between 20.5 – 43.5 gCO2eq/MJ, depending on feedstock, compared to CIs of 130 for “average U.S. Electricity” and 91 for gasoline and diesel. Furthermore, renewable propane can reduce nitrogen oxide and particulate matter from vehicle emissions, with newer-model autogas engines certified to exceed the EPA guidelines for MY-2027 vehicles.

The DOE reports that U.S. renewable propane production capacity is more than 4.5 million gallons a year based on Renewable Identification Number (RIN) transactions – a number that The Guardian article used to show the limited availability – but adds a disclaimer that “(a)ctual retail volumes of renewable propane are higher as renewable propane derived from certain feedstocks (e.g., pure soybean oil) do not qualify for EPA RIN credits and hence are not tracked by the EPA” – which was conveniently left out of that same article.

Production

In the real world, renewable propane production is much higher, but produced through processes or feedstocks that don’t qualify for the RINs. PERC predicts that renewable propane’s attributes and co-production status with biofuels, will “likely provide the ability to make renewable propane at scale.”

One production company in California is gearing up a new plant that is anticipated to produce approximately 13 million to 21 million gallons of renewable propane per year, and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that by 2030, California’s demand for renewable propane could reach 200 million gallons or more. The World LP Gas Association anticipates that renewable propane could meet half the world’s demand for non-chemical propane by 2050.

Renewable propane is chemically identical to conventional propane. The difference is that instead of being a by-product of natural gas production, renewable propane is a co-product of renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel.

One exciting innovation is the growing use of the camelina plant as a feedstock for renewable propane, biodiesel and SAF. Usage of camelina to produce biodiesel and renewable diesel is growing, with the backing of major renewable fuel producers such as Chevron Renewable Energy Group, because it has one of the lowest carbon scores and is capable of reducing GHGs by up to 60 percent. It is being welcomed in the agricultural sector as well, as it offers farmers additional revenue from fallow acres. As the production capacity for these fuels increase, renewable propane will scale alongside. Further, as the oil industry converts refineries to produce renewables, the potential for renewable propane will multiply.

Fueling More than West Coast Transportation

PERC’s February webinar on “Environmental Messaging” focused on ways propane retailers could educate their neighbors, customers and employees about the environmental benefits of propane. While the thrust of the program were the resources available on the advantages of traditional propane, renewable propane was addressed as well. PERC’s Bridget Kidd noted that “The more propane that is being used, the closer we are to achieving decarbonization goals across the country.”

Specific to renewable propane, the panelists agreed that it was not a question that customers were asking, quite possible because there was little-to-no availability in their regions. However, these propane retailers were including renewable propane when discussing the fuel’s uses beyond the barbecue grill, and as part of a cleaner future. Kidd summed it up, saying, “PERC is very active in the discussion and research around renewable propane and pathways to achieving renewable propane. That’s our primary focus. Renewable propane is real. There’s an element that’s both aspirational and inspirational with it. Propane’s a clean fuel and renewable propane just makes it that much cleaner. An abundant fuel that will just get that much more abundant with renewable propane.”

The NPGA estimates that only a fraction of the renewable propane currently being produced as a byproduct of other fuels is getting to market. Rather, it is being used to power the plants in which it had been produced. While this circular usage of a clean fuel is beneficial in many ways, current pricing and incentives could support the investments needed for loading racks and storage for that same renewable product and open up additional revenue for the plants and opportunities for renewable propane retailers.

Last year, the first renewable propane terminals opened in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and the city of Raleigh, North Carolina, began using renewable propane in its municipal vehicles to reach an 80 percent GHG reduction target by 2050.

Autogas – or propane used in vehicles – is the third most widely used alternative fuel in the world, with more than 28 million vehicles on the road worldwide. The Commonwealth of Virginia has contracted to convert vehicles to propane autogas, and enables their fleets to purchase blend of up to 20 percent renewable propane autogas.

Not all these gallons will end up in the transportation sector. In his response to The Guardian’s article, Forbes contributor and energy economist Dr. Talik Doshi noted that, “According to the 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, about 11 million U.S. households used propane as a major fuel and about 42 million U.S. households used propane for outdoor grilling.”

Since the chemical makeup of renewable propane is the same as conventional propane, it is compatible with existing propane installations. There is no need to change out or modify vehicle engines, tanks or heating systems. For home and building owners, this could offer a green alternative with a lower carbon footprint and significant savings when compared to replacing traditional HVAC systems with all-electric heat pumps and appliances.

In the October 2023 issue of Oil & Energy, Donald Montroy of Bergquist stated that, “renewable propane will easily move from mostly autogas applications today to space heating, water heating, electric-power generation and so on. More potential renewable propane applications, simply stated, means more opportunity for gallon growth.”

We have seen the transformation of heating oil to biofuels through blends of biodiesel and ultra-low sulfur heating oil. Similarly, traditional propane is now being blended with renewable dimethyl ether (DME). DME has been used as a nontoxic aerosol propellant and mixed with propane for heating oil and cooking fuel for decades. Renewable DME is produced from carbon captured out of the atmosphere. Theoretically, renewable DME, produced at scale from organic biogas, could be a pathway to removing carbon from the atmosphere at the same time it is producing fuel resources.

Propane is the third most widely used energy source in the U.S. by the number of households. Renewable propane could enable millions of propane users to continue to enjoy its versatility and comfort in lieu of expensive conversions to electric heating. What’s needed is for the production and distribution infrastructure to expand, and for states and the federal government to provide incentives for residential and commercial customers. “That’s where the largest market for propane exists,” the NPGA has said.