All

La Niña Is a Lock

by John Bagioni, Fax Alert Weather Service

But will this winter follow the historic path of past La Niña events?

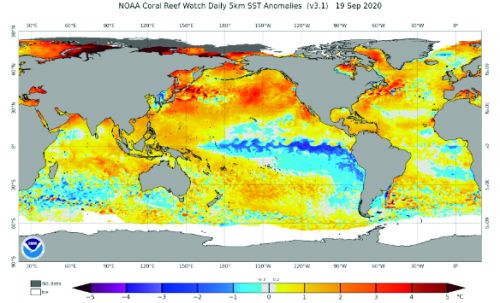

There is little or no doubt the upcoming 2020-21 winter season will feature a La Niña pattern across the equatorial Pacific basin. To review what this means, a La Niña event features a colder than normal sea-surface temperature pattern stretching across a significant portion of the equatorial Pacific basin. The satellite image shown here (Fig. 1) provides a look at the sea-surface temperature anomaly as of September 19.

Figure 1 depicts a classic La Niña signature with cold anomalies running from the west coast of South America westward into the west-central Pacific. Currently, the anomalies are solidly in the weak to moderate La Niña intensity levels. One of the many keys to the winter forecast will be frequent monitoring of the intensity trends of the cold anomaly, as well as the coverage of the cool pool. A stronger La Niña is more likely to follow the historic La Niña composites than a weak event.

It should also be noted that the current coverage of warmer than normal sea-surface temperatures across the globe remains immense, especially across the Northern Hemispheric oceans. I’ll have more on this later, but the continual warming of the global oceans has to be part of the mix when discussing the upcoming winter season and is one of several reasons why I am starting to really doubt the validity of some of the old rules about La Niña or El Niño events.

That being said, we have to use the historic La Niña composites as a baseline and then try to use other global oceanic and atmospheric indicators and trends to adjust La Niña composites, as the late fall season unfolds.

______________

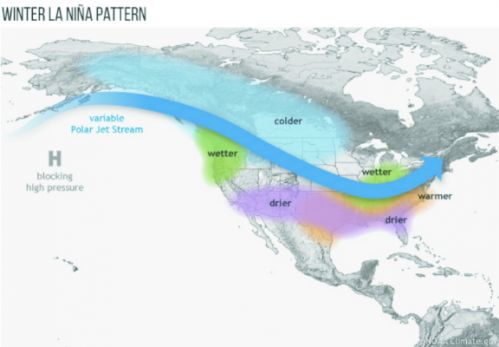

Figure 2 shows the basic La Niña composite, as it relates to temperature and precipitation trends during the course of a winter season.

As depicted on Figure 2, the “normal” La Niña composite shows a strong potential for two main outcomes, in terms of temperature anomalies. First, warmer than normal conditions “often (not always)” set up from the Southern Plains eastward into the Southeast on northward across the Middle Atlantic. Colder than normal conditions are favored from northwestern Canada southeastward into portions of the Northern Plains.

In terms of precipitation, the composites show wetter than normal conditions occurring across the Pacific Northwest, as well as much of the Midwest and Ohio Valley regions. Drier than normal conditions would usually be favored from the Southern Plains eastward into portions of the Deep South and Southeast.

If past La Niña events can be believed, the winter jet stream averaged configuration (the blue arrow on Figure 2) will feature a mean upper level ridge across the northeast Pacific, near or just south of Alaska. Meanwhile, a mean upper level trough would position itself over the Midwest. But as always, the depicted jet stream configuration represents the winter average. As we well know, small shifts in the composite averaged jet flow can — and often do — produce markedly different sensible weather outcomes.

____________

While the La Niña composite indicates a warmer than normal zone from the Southern Plains on eastward into the Middle Atlantic region, the question then becomes how far north the warmer than normal zone extends into the Northeast?

Many forecasters — at least from what I have read so far — favor the solidly warmer than normal wintertime conditions covering much of the Northeast (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and New England). Given the trends for the past several years, that may very well be the safe play. But there are ways that the basic La Niña can be altered due to other global patterns. If the northeast Pacific/Alaskan upper level ridge ends up farther east than the composite shows, then the cold air feed into the continental U.S. will be displaced eastward, closer to the Northern Plains and western Great Lakes region. Instead of the area from Montana into the Dakotas being favored for the best cold air entrance point, the Upper Midwest might be favored. That type of shift can dramatically alter how far north the warmer than normal zone extends across the eastern states. It would only take a minor shift in the northeast Pacific/Alaskan upper level ridge axis to keep most of the warmth bottled up in the Deep South and/or Southeast states.

Over the past several winters I have been harping about the position of the warmer than normal ocean temps across the northeast Pacific. The position and strength of northeast Pacific and/or western Canadian upper level ridging can be impacted by the location and extent of the warm pool. It is certainly not a perfect correlation, but in the past I have favored a solidly warmer than normal sea-surface temperature configuration positioned across the northeast Pacific and along the western Canadian coastline. However, while these warm pools have shown up during the fall for the last two years, they have managed to weaken and shift westward further offshore as we moved into the early winter. With that westward shift, the potential for long-lasting western Canadian ridging diminished. I do not think the warm pool is the only reason for the existence of western Canadian ridging, but I do believe it can help sustain it. Once again, as we head into the fall season, we see lots of warmer than normal water sitting across the northeast Pacific and off the west coast of Canada (Figure 1). In my mind, that has always been a good sign. But, as just stated, in recent years the warmer than normal conditions have managed to fade as we moved through the fall on into the early winter period. If that happens again, it will be hard to run away from the basic La NiÒa composite, which suggests warmer than normal eastern U.S. wintertime conditions.

Assuming we do see a weak to moderate La Niña this winter — and at this time there is no reason not to believe one will be in place — we have to consider the long running potential for strong western Atlantic/Southeast ridging. Southeast/western Atlantic ridging has been a frequent hindrance to eastern cold for several years. A ridge in this position not only acts as a block to southeastward/eastward moving cold air intrusions, it frequently promotes a stream of warmer than normal conditions up the Eastern Seaboard on into much of the Northeast. Currently, as seen in Figure 1, the western Atlantic is running warmer than normal, which implies an ocean profile conducive to western Atlantic upper level ridging. Of course, just like a warmer than normal northeast Pacific does not guarantee western Canadian upper level ridging, a warmer than normal western Atlantic does not mean strong ridging is a lock to develop along or just offshore of the East Coast. Nevertheless, you have to at least give these anomaly correlations some credence.

________________

As we move into and through the mid-fall period, the emphasis will be on monitoring the intensity and coverage of the La Niña sea-surface configuration, the state of the northeast Pacific and western Atlantic warm pools and advance of high latitude snow cover. All of these trends can be used to consider modifications to the historic La Niña composite.

Also, there will be a need to assess and monitor the developing fall storm track. While the La Niña composite hints at drier than normal wintertime conditions, there are numerous La Niña events that have produced normal to above normal snowfall across the Northeast. If an active East Coast winter season evolves, that could help skew the Northeast winter temperatures closer to normal even if the winter overall still ends up with a positive anomaly. This would be especially true for Upstate New York and Northern New England.

In summary, a La Niña winter is expected. The composite of La Niña events suggests a warmer than normal winter from the Southern Plains on eastward into the Middle Atlantic with the potential for warmer than normal conditions to spread northward across much of the Northeast. The greatest likelihood for colder than normal conditions appears to be across the Northern Plains on northwestward into western Canada and parts of the Northwest. With all that being said, we still need to examine whether or not the old rules of La Niña and/or El Niño events still hold. We have seen the last two winters feature weak El Niño conditions that did not follow classic El Niño rules. Climatic shifts that are underway may make some of the old rules useless. There are no guarantees that this La Niña event will behave exactly as historic composites indicate. Obviously, we have more to discuss as the season continues.

John Bagioni provides 10-day temperature and heating degree day forecasts, storm updates, and webinars to heating fuel dealers via the Northeast Energy Weather Service, available at a 50-percent discount to NEFI members. Visit nefi.com/join to join NEFI and nefi.com/store to sign up for the Northeast Energy Weather Service.

Related Posts

U.S. Competing to Secure Critical Minerals

U.S. Competing to Secure Critical Minerals

Posted on June 16, 2025

The Clean Air Act, the EPA, and State Regulations

The Clean Air Act, the EPA, and State Regulations

Posted on May 14, 2025

Day Tanks Support Back-up Generators in Extreme Conditions

Day Tanks Support Back-up Generators in Extreme Conditions

Posted on March 10, 2025

Major Breakthrough in Lithium-Ion Batteries

Major Breakthrough in Lithium-Ion Batteries

Posted on February 12, 2025

Enter your email to receive important news and article updates.