All

First Look: Winter 2022-2023

by John Bagioni, Fax-Alert Weather Service

A third-consecutive La Niña is in place for only the fourth time on record

This will be the third consecutive winter season with a La Niña signature in place across the equatorial Pacific. It appears there have only been three similar scenarios to this Pacific signal: 1956-57, 1975-76 and 2000-01.

While these three analog years will be used as a baseline, ongoing climate change factors mean it is unlikely 2022-23 will mimic these analogs perfectly. However, they should offer some guidance.

Note: we are still very early in the winter season forecasting game so it is critical to understand this is a preliminary outlook. We may need to adjust and modify this discussion, maybe significantly, in the weeks and months to come.

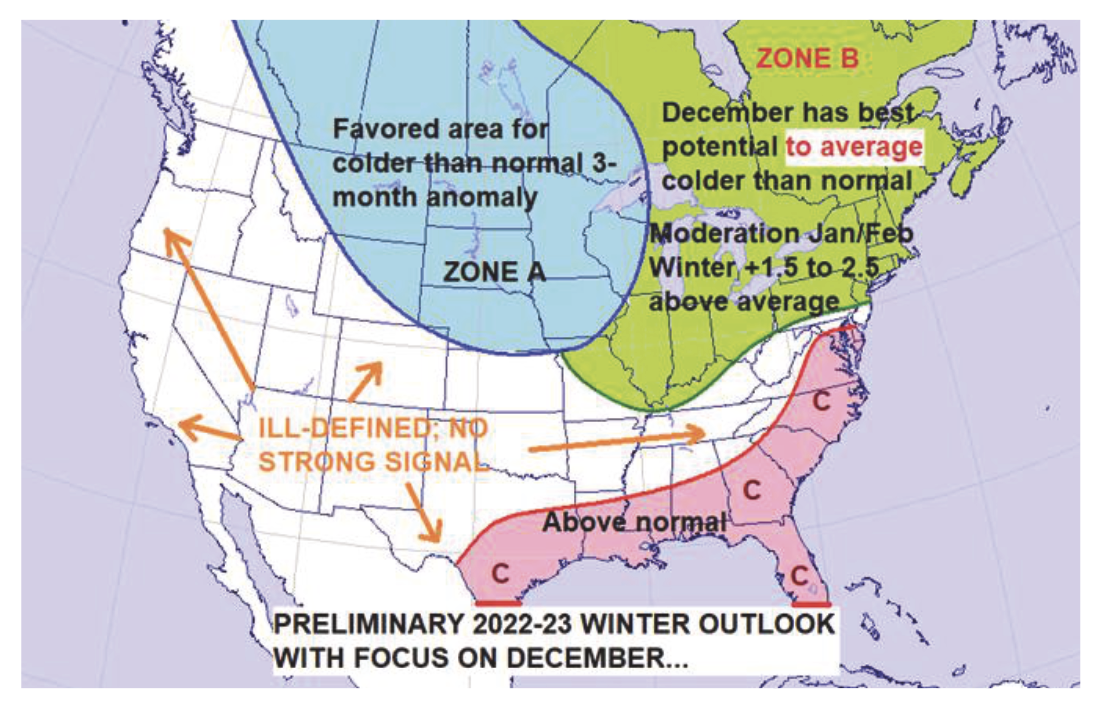

Nonetheless, this article offers some core conclusions for the upcoming 2022-23 heating season — given early modeling trends — especially for the December period. We’ll begin with a quick overview of my “first call” map below followed by an analysis of the factors that are likely to drive the pattern.

Zone Breakdown

ZONE A: Many, not all, La Niña winters try to manufacture a solidly colder than normal zone from the Northern Rockies on south and east across the central and Northern Plains into parts of the western and northern sections of the Midwest and western Great Lakes.

I see no reason not to look at ZONE A as the zone most likely to experience a colder than normal winter season.

As stated many times in past articles, La Niña winters usually produce significant temperature anomaly shifts from month to month. I would expect ZONE A to see a one-month period cold enough to skew the three-month winter average to the cold side of normal — even if there is significant moderation during the other winter months. As to which month or period that might be, keep reading!

I suspect the overall best cold potential exists in the area from the Northern Rockies on south and east across the central and northern portions of the Plains and western areas of the Midwest and Great Lakes.

ZONE B: Once into the central portions of the Midwest and Great Lakes on eastward across the Ohio Valley, northern Middle Atlantic, New York and New England, I think the 2022-23 winter season will be quite variable, as competing La Niña forces battle it out (more about this later as well).

While my current take is to keep the three-month winter average across Zone B in the +1.5 to +2.5 degrees warmer than normal range, how we get there is a complex issue. Almost all La Niña winters feature a significantly colder than normal period, and I expect one such period this winter. Right now, there is multi-model support for December 2022 to be the coldest month of the three-month period.

How cold it will be and how quickly the reversal into a normal or solidly warmer than normal pattern evolves once into January/February 2023 is the tough call. For now, the main point is there are multiple signals for at least a normal if not significantly colder than normal December followed by some degree of moderation once into 2023.

ZONE C: Above, I highlight only a fairly small area where there appears high confidence for above normal winter temperatures. Most La Niña events eventually go on to produce extensive warmer than normal zones, but I am not yet overly confident where those areas will develop. Central and Southern California on eastward across the southern Rockies into the Southern Plains could be a good candidate, but for now, southeastern Texas on along the Gulf Coast into Virginia is my call.

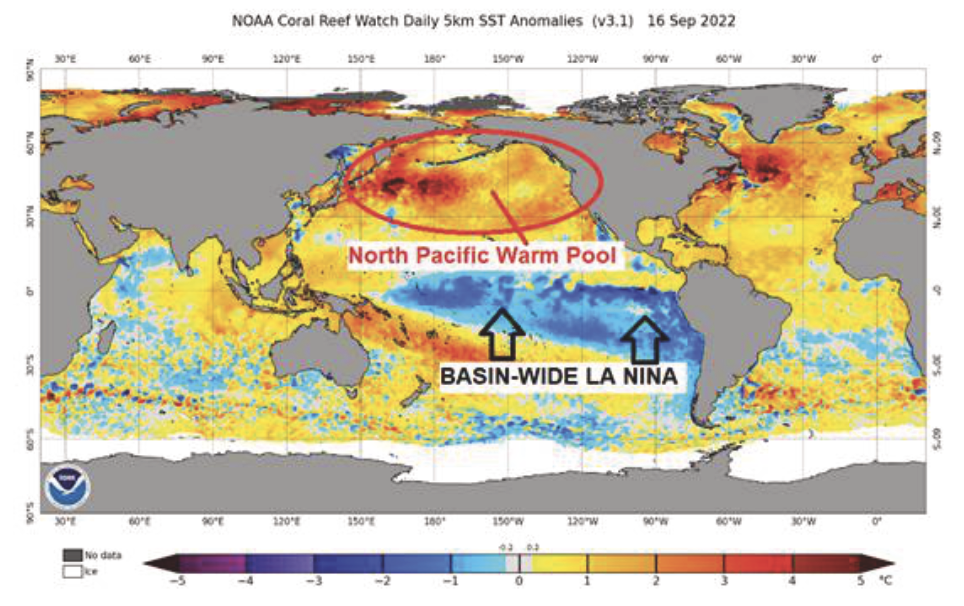

Nowhere to Go But Up

Here is a recent image of the sea-surface temperature anomalies. The La Niña signature is about as solid as I have ever seen, stretching from the west coast of South America westward to almost 150-East. We are dealing with a basin-wide event. There had been some thought late last spring that we would be transitioning into either a fading, weak La Niña or a weak El Niño (warm equatorial Pacific). That is not the case!

We are likely going to see some steady weakening of the La Niña as we progress through the winter season. How could we not? The cold anomalies associated with the La Niña are about as cold as they get on a widespread basis. There is nowhere to go but up.

Once again, we are noting extensive warm anomalies across the North Pacific. I have always viewed the warm anomalies favorably in terms of cold air delivery into the U.S., but in recent years they have not lived up to expectations.

I like seeing warm anomalies across the North Pacific, but I am no longer viewing them as a strong signal or lock to ensure frequent cold air delivery into the U.S. I don’t think they hurt, but it has become obvious they are not the “be all, end all” to cold winters. Also, just because they are present in September does not guarantee they will be around come January.

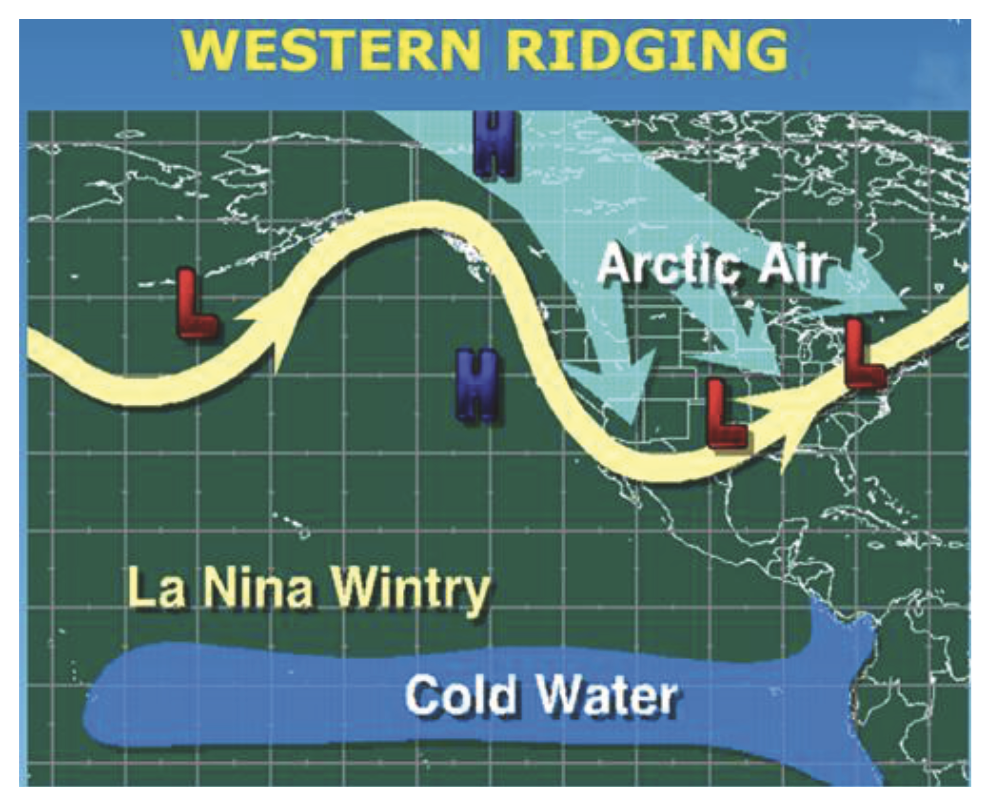

Western Ridging

One of the most important keys to a La Niña winter is the position and strength of the eastern Pacific/western Canadian upper-level ridge. When it is close to the western Canadian coastline or even a bit inland, it opens the door to direct discharges of Arctic air into the north-central U.S.

How far northward into the Polar Regions that ridge extends will greatly impact the intensity of arctic intrusions. If the pattern favoring far eastern Pacific upper-level ridging is a frequent occurrence, it can change the entire tenor of the winter season since arctic intrusions would become commonplace. Moving forward into early December, one of the keys will be charting the frequency of the eastern Pacific/western Canadian ridge setup.

Ridge or Trough?

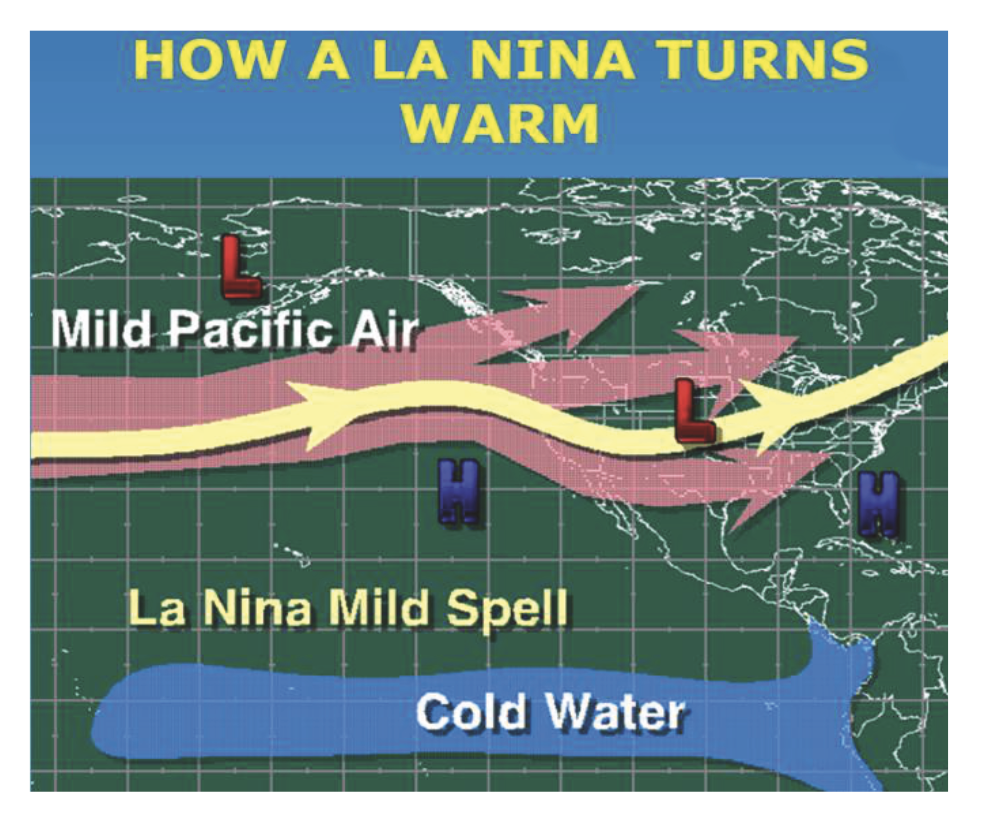

When the eastern Pacific pattern favors upper-level troughing the outcome reverses.

If upper-level troughing exists across the eastern Pacific, or if the Pacific pattern goes flat (zonal), the pattern across the country tends to feature widespread milder than normal conditions. The presence of an eastern Pacific trough allows Pacific air streams to dominate North American pattern. This essentially shuts off the arctic intrusions and allows Pacific based air masses to control the temperature pattern across the Lower 48.

Most La Niña winters feature alternating periods of eastern Pacific ridging and troughing. If upper-level ridging periods are more frequent than troughing periods, the potential for the winter to feature more widespread and persistent cold conditions increases. But if upper level troughing (across the eastern Pacific) is the favored mode, milder conditions will have the upper hand.

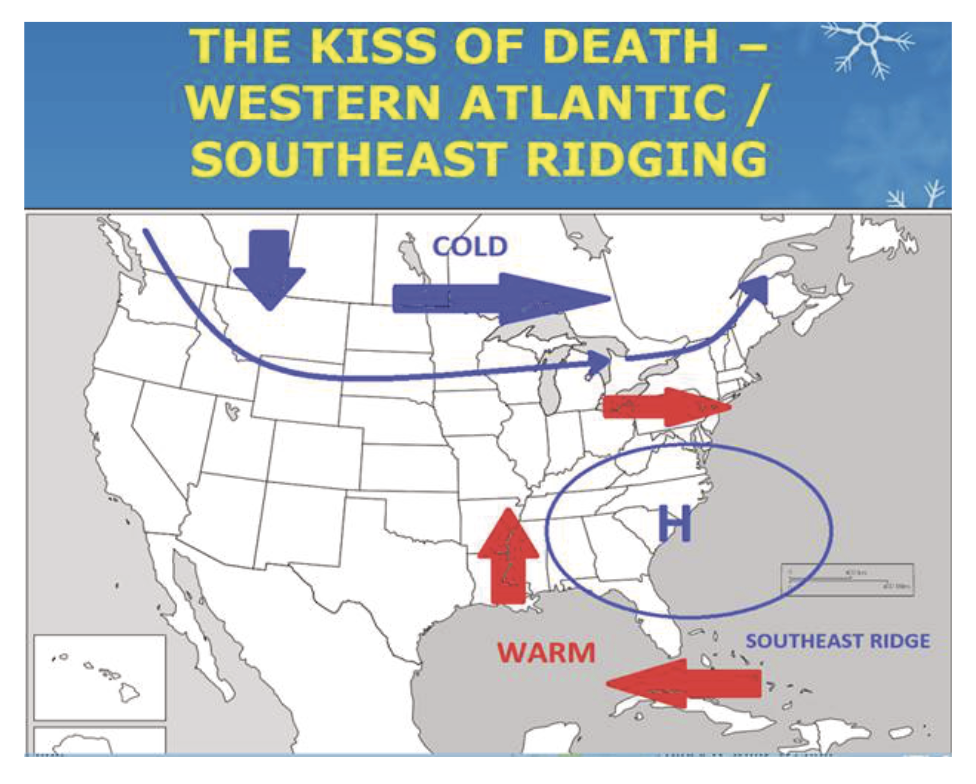

The Kiss of Death

A major factor in how effectively cold air can spread eastward across the northern tier and central portions of the U.S. during a La Niña winter has to do with the strength, position and frequency of the Southeast Ridge. If you want extended cold periods across the eastern and northeastern sectors of the country during the winter season, a strong Southeast/West Atlantic ridge is usually the “Kiss of Death.”

A strong Southeast ridge effectively blocks cold air masses from moving east and southeastward out of the Northern Rockies and Northern Plains, and forces them on a more east/northeasterly heading across southern Canada. This tends to prevent extended colder than normal periods from becoming established across most of the eastern U.S., including New York and New England.

If the ridge stays just far enough offshore, arctic intrusions during the upper-level ridge mode of the La Niña winter can get into portions of the Northeast, especially areas close to the Canadian border.

La Niña winters have historically produced periods of Southeast ridging so there is always a risk of extended milder than normal periods. But small shifts in the intensity and location of the Southeast ridge can allow for portions of the Northeast and Upper Midwest to stay close to normal or even somewhat colder than normal.

Either way, there is no denying the warming role a Southeast ridge can play during a La Niña winter.

High Latitude Blocking

Whether or not the high latitude jet stream flow becomes blocky (well defined, closed upper-level troughs and/or ridges), or features a steady, fast-moving west-to-east flow is a critical question.

High latitude blocking is usually favorable for arctic intrusions into the mid-latitudes. Fast west-to-east flows across the high latitudes are not good for blocking and often lead to milder than normal conditions. High latitude blocking is usually very poorly forecasted weeks or months in advance. I do think we will see some periods of blocking, but how long-lasting and how effective it is in maintaining arctic intrusions is unknown.

I will expand upon this further in a bit, but there are early signs of a strong North Atlantic blocking (-NAO) episode early this winter (late November and December). If that becomes the case, it would be reasonable to favor a cold and early start to the winter across portions of the Midwest and Northeast, including New England.

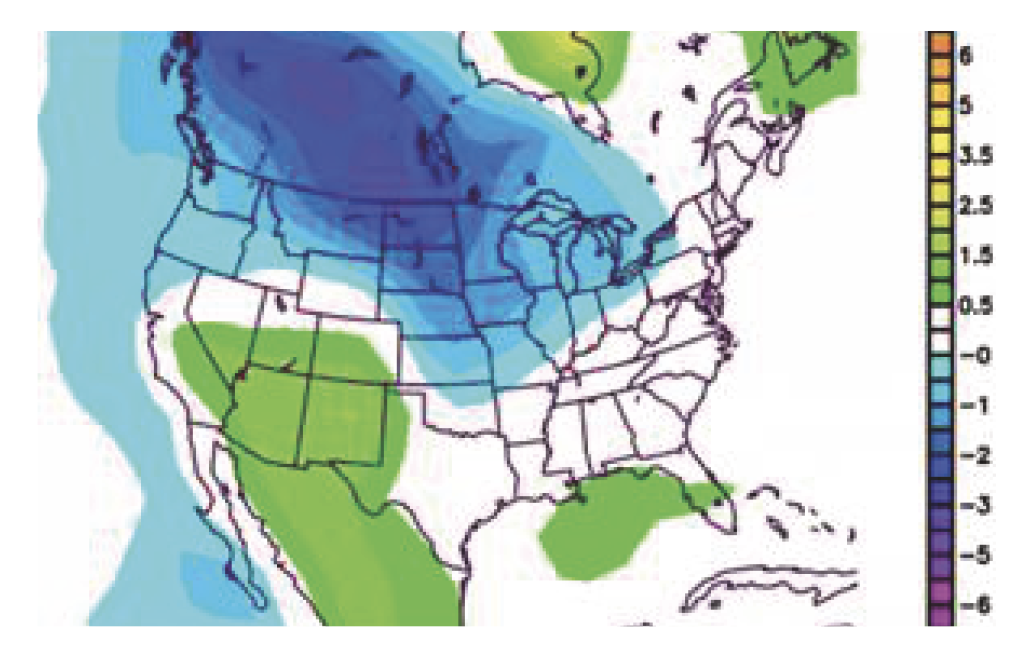

General La Niña Analog

As for a general analog, this basin-wide La Niña composite is a good starting point. Here is the temperature composite.

Note the general cold air zone mimics what I plotted on my First Call Map. It is interesting to note there is a lack of widespread above normal zones across the east. There is a hint of warming along the Gulf Coast, which I increased in coverage on my map. The Southwest and southern Rockies are projected as the warmest zone overall, but I have not been as bullish there.

The cold air bleeding southeastward from western Canada into and across the Northern Rockies, Northern Plains into the western Midwest and Great Lakes shows up nicely on the composite map. This is very typical of La Niña winters. The question then becomes how intense will cold periods be across these areas. The next question is how effective will the cold transport be into the Northeast.

It must always be remembered that the composite is a snapshot of the 90-day (three-month) average. La Niña patterns are a tug-of-war between cold and warm periods. It never means a particular region is continually colder than normal, nor warmer than normal. Big three-to-four-week reversals are the norm.

What Can the 2020-21 & 2021-22 La Niña Winters Tell Us?

While both of our past two winters featured La Niña events, they took different tracks. Both featured significant cold to warm or warm to cold reversals, and both featured an extended cold period.

Winter 2020-21 featured a warm December and a transitional January followed by a very cold February. Winter 2021-22 also featured a warm December, but January 2022 went on to become the coldest month of the season.

The past two winters’ three-month averages featured zones of significantly colder than normal conditions, along with some well above normal areas. The 2020-21 winter was warm along the northern tier on into the Northeast, even though a widespread cold-to-bitter-cold February occurred. Meanwhile, the 2021-22 winter saw a decidedly colder than normal three-month average across the far northern tier of the U.S., with even parts of far northern New England and New York averaging a bit colder than normal.

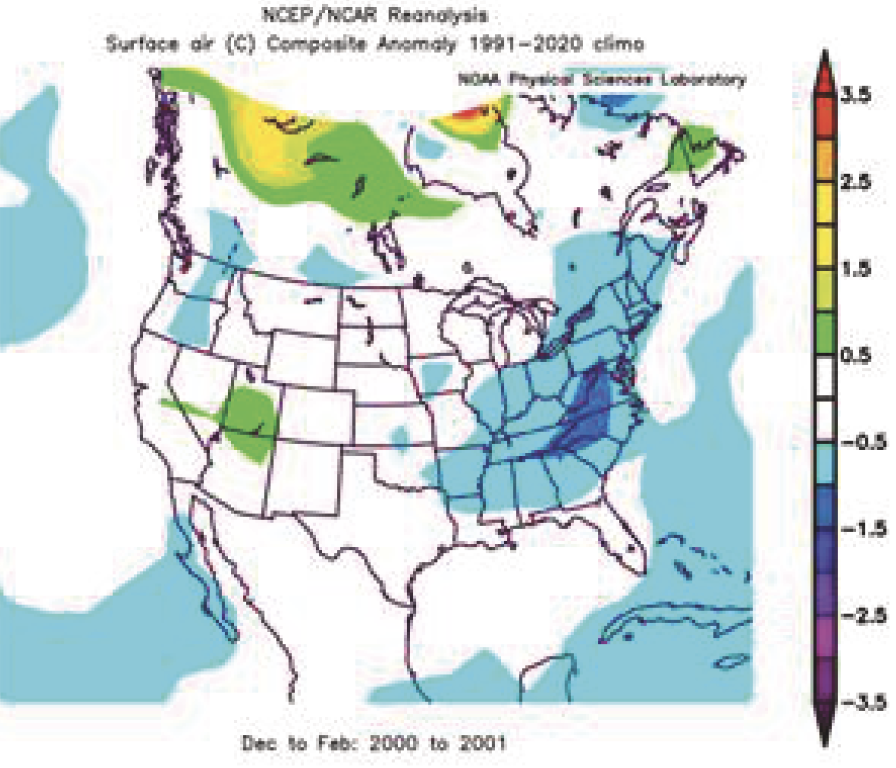

Third-Year La Niña Winters

The 1956-57 winter was very cold across Canada, warm across the southern U.S., and cool/cold across the northern tier. There was tons of cold weather across Canada but Southeast ridging kept it there!

In the 1975-76 winter, the cold once again bottled up across Canada. The warmth across the Southeast likely reflected a strong or at least frequent Southeast ridge.

Lastly, here is the 2000-01 winter. Cold across the Southeast and East suggest the Southeast ridge was not a big player. Canada looks fairly bland, which means poor western ridging.

All three analog winters for third-year La Niña events featured at least one solid cold period during January/February. The more interesting thing about the analog winters is that two out of the three featured a solidly colder to much colder than normal December.

December 1975 was modestly colder than normal. December 2000 was very cold. December 1956 featured normal to slightly warmer than normal conditions.

I bring up the December factor since we have multi-model agreement that December 2022 will feature colder than normal conditions across the Midwest, Great Lakes and Northeast, assuming a persistent -NAO develops.

Whether or not the model agreement about December is correct is tough to say with high confidence right now. However, all of the modeling is showing strong North Atlantic blocking starting in late November and continuing well into if not through December.

Decembers have struggled to run colder than normal for several years now, and it is tough to go all in on the cold being suggested by the modeling. But it also hard to ignore, and it must be seriously considered.

Last year there appeared to be multiple analogs suggesting a cold December, but that failed miserably. This year is a little different since the December forecast for cold is predicated on multiple model suites and runs predicting North Atlantic blocking. It is not based on an analog method. If the modeling is correct about the North Atlantic blocking, a cold December will ensue.

Key Takeaways

If you take nothing else from this early winter outlook, consider these key points.

- A basin-wide La Niña expected this winter.

- The Northeast region is expected to have a three-month temperature anomaly of +1.5 to +2.5 degrees.

- The greatest potential for extended colder than normal conditions across the Northeast is favored to occur from very late November on through December.

- The January/February period in the Northeast is likely to feature variable conditions with multiple transitions in and out of above normal conditions and colder than normal conditions over seven-to-10-day periods. Overall, this period is expected to average at least modestly warmer than normal (+2.0 to +3.5 degrees) across the Northeast.

- While at least one extended solidly colder than normal period is likely across the Northeast during the second half of the winter, I would still expect a noteworthy warm period to develop across the Northeast, as has been the case during the last two La Niña events. There has been a tendency for La Niña warm periods to be underestimated each of the last two years and we should be wary of this happening again.

- The coldest area of the country this winter is expected to run from the Northern Plains east/southeast into portions of the Midwest and Great Lakes. How effectively the cold can filter eastward into the Northeast during the second half of the winter is a tough call and will be depend on keeping the Southeast Ridge weak.

John Bagioni provides 10-day temperature and heating degree day forecasts, storm updates and webinars to heating fuel dealers via the Northeast Energy Weather Service, available FREE to NEFI members with their annual dues. Visit nefi.com/join to join NEFI or email benefits@nefi.com for more information.

Winter Storm/Snowfall Potential

First, for a more detailed winter storm outlook, let’s wait to see how the hurricane season and mid-fall coastal storms play out.

I have noted in the past that La Niña winters tend to stay fairly close to long-term averages for Northeast and New England winter snowfall totals.

The variable nature of La Niña temperature patterns can open the door to some very big events, normally in areas north of New York City especially western and northern New York on across northern New England.

That being said, last year we did see some very significant Mid-Atlantic winter storm action.

Highly variable conditions were noted last year across much of eastern New York and New England with zones of normal to above normal snowfall not very far away from areas of well below normal snowfall.

As is often the case, during any given winter week, very slight shifts in an atmospheric setup can make all the difference between a miss or minor event and an all-out blizzard.

Last year featured one very big eastern New England blizzard that contributed to portions of eastern Massachusetts ending well above normal for snowfall while areas to the west ended up near normal or well below normal.

I will say, though, if we do indeed end up with a December -NAO feature, that month would be favored to feature some significant early winter snow. We have not had a truly cold and snowy December in quite a few years, so maybe this third consecutive La Niña winter will be the charm.

Related Posts

From Blue Flame to Biofuels

From Blue Flame to Biofuels

Posted on June 25, 2025

HEAT Show Announces Fenway Park Backyard BBQ

HEAT Show Announces Fenway Park Backyard BBQ

Posted on May 15, 2025

Delivering New York City’s Clean Energy Solutions

Delivering New York City’s Clean Energy Solutions

Posted on May 14, 2025

Are You a Leader or a Boss? The Choice is Yours

Are You a Leader or a Boss? The Choice is Yours

Posted on May 14, 2025

Enter your email to receive important news and article updates.