How a coalition defeated policy backed by three states, every utility in the Northeast, BP, Shell and Ford

Last November, CEMA helped defeat a climate initiative that could have put the heating fuel industry out of business in the Northeast. The association was a key member of a multi-state coalition including trade associations, nonprofits and allied politicians.

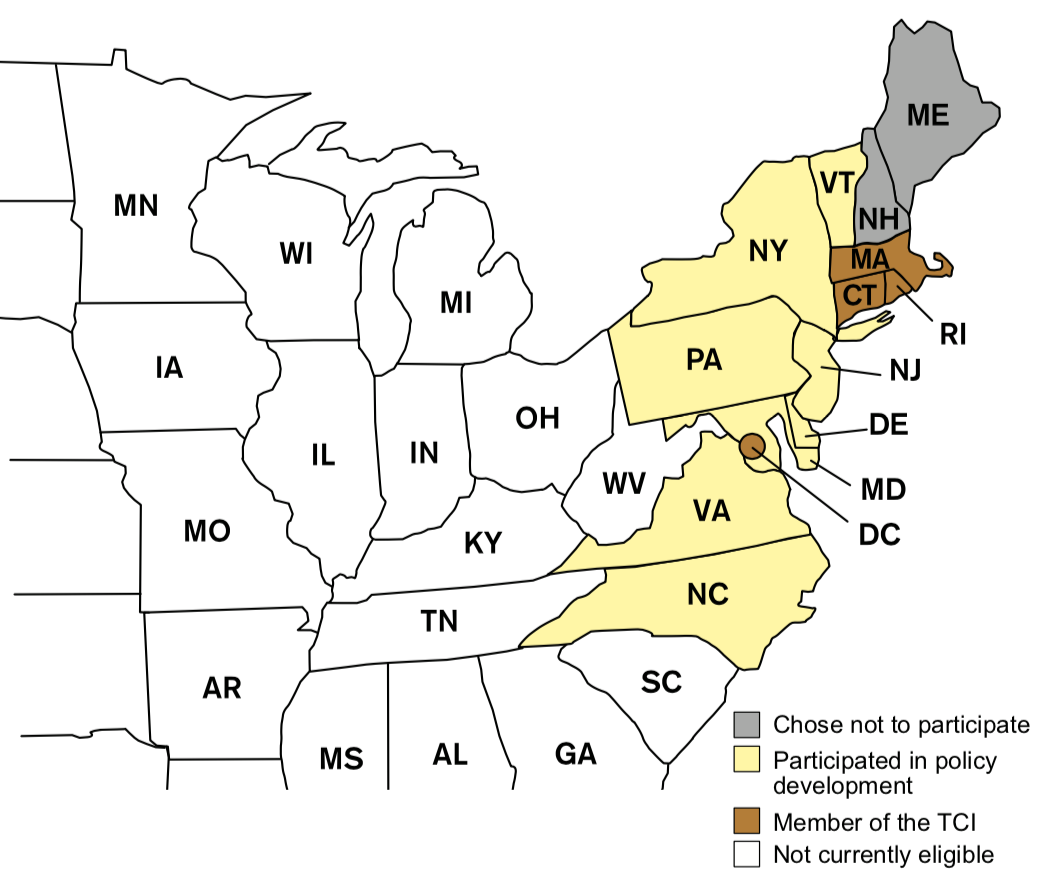

This coalition succeeded in staving off a program called the Transportation Climate Initiative (TCI), initially signed by Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia. The purpose of TCI was to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the transportation sector. It would achieve this by doing two things: taxing diesel and gasoline through an auction process where fuel distributors would have to bid for the right to sell fuel; and reducing the amount of diesel and gasoline that could be sold in participating states by 30% over 10 years.

Though heating fuel wasn’t included in TCI, it would have been ruinous for heating fuel dealers since their delivery trucks run on diesel. Not only would the cost of diesel rise over time due to the tax, but there would be at least 30% less available, leaving fleets of vehicles stranded without fuel.

While TCI was conceived in 2010, it wasn’t until 2018 that nine states — Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia — and the District of Columbia agreed to pursue a plan to develop TCI further. Of these nine, eventually only Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Washington, DC in 2020 decided to actually implement TCI. By this time, Maine and New Hampshire had withdrawn, and the other states took a wait-and-see attitude. To make the multi-state program viable, it was thought that TCI needed to be adopted by at least three states. Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island would be the “guinea pigs.” Massachusetts could enter TCI through executive action by its governor while Connecticut and Rhode Island required adoption by their legislatures. Washington, DC was fully committed, but as a minor player, it still needed the other three states to adopt TCI.

As early as 2016, CEMA began discussing TCI internally with its members. As TCI advanced and Connecticut became more engaged, we ramped up our efforts. With prior experience working on state and federal election campaigns, CEMA staff was aware of the old political adage: define your opponents before they have a chance to define themselves. We began with extensive press outreach, calling TCI a tax on gasoline and diesel in 2020 as soon as Connecticut Governor Lamont signed the TCI Memorandum of Understanding.

As expected, a bill was raised in the legislature in 2021 to implement TCI. We testified at hearings and lobbied legislators. We worked with allies in the legislature and with private think tanks. Our primary effort to brand TCI as a tax on fuel was completely successful. TCI proponents went to great length to say TCI was not a tax. One media headline read “Is it a plan to fight climate change, or a gas tax?” One of TCI’s planners said defensively, “It’s not a tax. Categorically, it’s not tax!” But the more they protested, the more TCI became associated with taxation, and we won that debate every time. Ultimately these efforts led to legislative leaders withdrawing the bill, with even the Democratic president of the State Senate calling TCI a “regressive tax.”

While we won the battle, the war wasn’t over. Despite victory in the legislature, there were calls all summer to hold a special session in the fall to adopt TCI. Environmental groups pushed hard for this, running ads and hiring powerful lobbyists. Even some mega-corporations, including British Petroleum, Shell and Ford, were lobbying for TCI, running advertising all spring and summer. And efforts were still underway to advance TCI in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. CEMA countered through the media. We worked with influential bloggers, libertarian advocacy groups, and industry allies, including the Energy Marketers Association of Rhode Island (EMARI).

The messaging for TCI, meanwhile, was constantly evolving, which made it something of a moving target for us. While it initially started as a climate change initiative, Connecticut’s governor said it was a transportation infrastructure bill to replace his highway toll proposals that failed in 2019. Then one advocate called TCI “a tool to advance racial justice Ö by shifting power and resources to Black and Brown communities who have suffered the most from air pollution and a lack of access to equitable transportation options.” Then the messaging shifted again, claiming TCI would solve a growing health problem and save thousands of children dying from asthma.

So our argument changed too. For budget-conscious legislators, we demonstrated that the loss in fuel tax revenues from reducing fuel sales by 30% would create a big budget deficit, not offset by TCI revenue. We talked about how the TCI auction system would create fuel shortages in Connecticut above and beyond the planned 30% reduction.

The early fall came and went and still no special session on TCI. By now, the question was whether Governor Lamont would bow to environmental pressure and call for TCI to be adopted in 2022, an election year. In the end, Lamont was saved from having to make this decision, because Congress passed their infrastructure bill, giving Connecticut billions of dollars in infrastructure spending, and because the recent spike in gasoline prices made a new fuel tax even more unpalatable. Now was not to the time to add a TCI tax on top of this, Lamont announced at a November 16 press conference.

With Connecticut’s fall, Massachusetts and Rhode Island were not far behind. Throughout the year, CEMA worked against TCI in those states as well, knowing that if it were to fail in just one of them, it would fail in Connecticut too. As it was, it failed in Connecticut first, so the other states soon fell like dominoes. On November 18, two days after Lamont pulled the plug on TCI, Massachusetts Governor Baker announced he was pulling out for the same reasons Connecticut cited. And two days after that, on November 20, Rhode Island inevitably dropped out too.

Fighting TCI was a team effort, especially as we were opposed by the full weight of three state governments, the environmental lobby and all the utilities, as well as mega corporations like Shell, BP and Ford. So we thank all our allies in this fight! While it’s unlikely TCI will be resurrected this year, you can be certain TCI advocates will redouble their efforts in 2023. We need to be ready for this, as only “eternal vigilance is the price of freedom.”

Chris Herb and David Chu are, respectively, President and Vice President of the Connecticut Energy Marketers Association. They can be reached at chris@ctema.com, chu@ctema.com, or 860-613-2041.

TCI Auctions & You

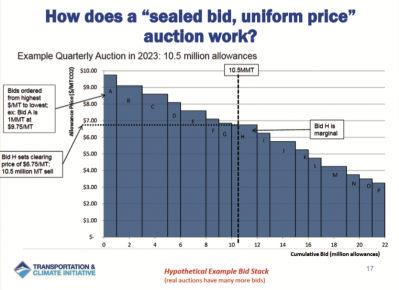

The diagram above shows how a TCI auction works according to the Georgetown Climate Center, which created the program. Imagine a big Ebay auction. You bid on a CO2 allowance, which enables you to sell a metric ton of CO2 generated by fuels, which equates to 127 gallons of gasoline or 97 gallons of diesel.

Each of the bars in the chart represents a bid by a fuel supplier. The height of the bar represents the bid price. The vertical dotted line represents the winning bid price. The final auction price is the “tax” that is passed onto customers. Bidders to the left of the line win their bid. Those to the right underbid, and so lose their bids. But this means they get no allowances with which to sell fuel. That means they either go out of business, or they have to buy allowances from the winners who might be their competitors. Winners might not want to sell to losers since they may want to stock up their excess allowances for when the supply is reduced in following years (remember the supply is reduced 30% over 10 years). Or they may not want to sell to smaller competitors, hoping to drive them out of business, or might sell to them at a high markup.

a bid by a fuel supplier. The height of the bar represents the bid price. The vertical dotted line represents the winning bid price. The final auction price is the “tax” that is passed onto customers. Bidders to the left of the line win their bid. Those to the right underbid, and so lose their bids. But this means they get no allowances with which to sell fuel. That means they either go out of business, or they have to buy allowances from the winners who might be their competitors. Winners might not want to sell to losers since they may want to stock up their excess allowances for when the supply is reduced in following years (remember the supply is reduced 30% over 10 years). Or they may not want to sell to smaller competitors, hoping to drive them out of business, or might sell to them at a high markup.

Companies needing diesel for their trucks would be especially hard hit. Because the bids are for CO2 allowances, one allowance would buy more gasoline gallons than diesel gallons, making it more efficient for bidders to spend their allowances on gas than diesel, exacerbating diesel shortages even more so.