The Future of Renewable Liquid Fuels

Reaching net-zero carbon emissions has been the stated goal for the renewable liquid heating fuels (RLHF) industry for the last six years, but many individuals, organizations, and companies have been aiming for net-zero for much longer. However, at the HEAT Show, we learned that the industry is poised to go beyond net-zero, and deliver on the promise of negative-carbon solutions.

Some of the advances discussed at the Show were well known, such as the availability of B100-rated burners and boilers. But other news came as a surprise, such as the announcement of negative-carbon results from the NET-0 homes in the National Oilheat Research Alliance’s (NORA) research project and the introduction of ethyl levulinate (EL), a negative carbon liquid fuel, from Biofine. The potential for B100 and renewable diesel (RD) in heating and transportation were topics of discussion as well.

So many avenues, so many opportunities.

The Negative-Carbon Home

During his presentation, Michael Devine, NORA President, reviewed the successes of NORA’s NET-0 home project.

Before upgrading to a high-efficiency Energy Kinetics boiler and photovoltaic solar panels, the average home created approximately 22,036 pounds of CO2. The heating system produced more than 16,080 pounds, and the electricity used created another 5,995 pounds of CO2 for a total of 22,036 pounds of carbon produced per year.

The switch to B100 fuel produced an immediate 80 percent reduction in emissions, to only 2,680 pounds. The solar panels produced more than 10,000 kWh enabling the home to return clean energy to the grid. The difference between the amount of carbon emissions from grid electricity before and after installation of the photovoltaic panels, and adjusted for the emissions produced by the heating system, netted a savings of nearly 2,000 pounds of CO2 per year.

The Negative-Carbon Fuel

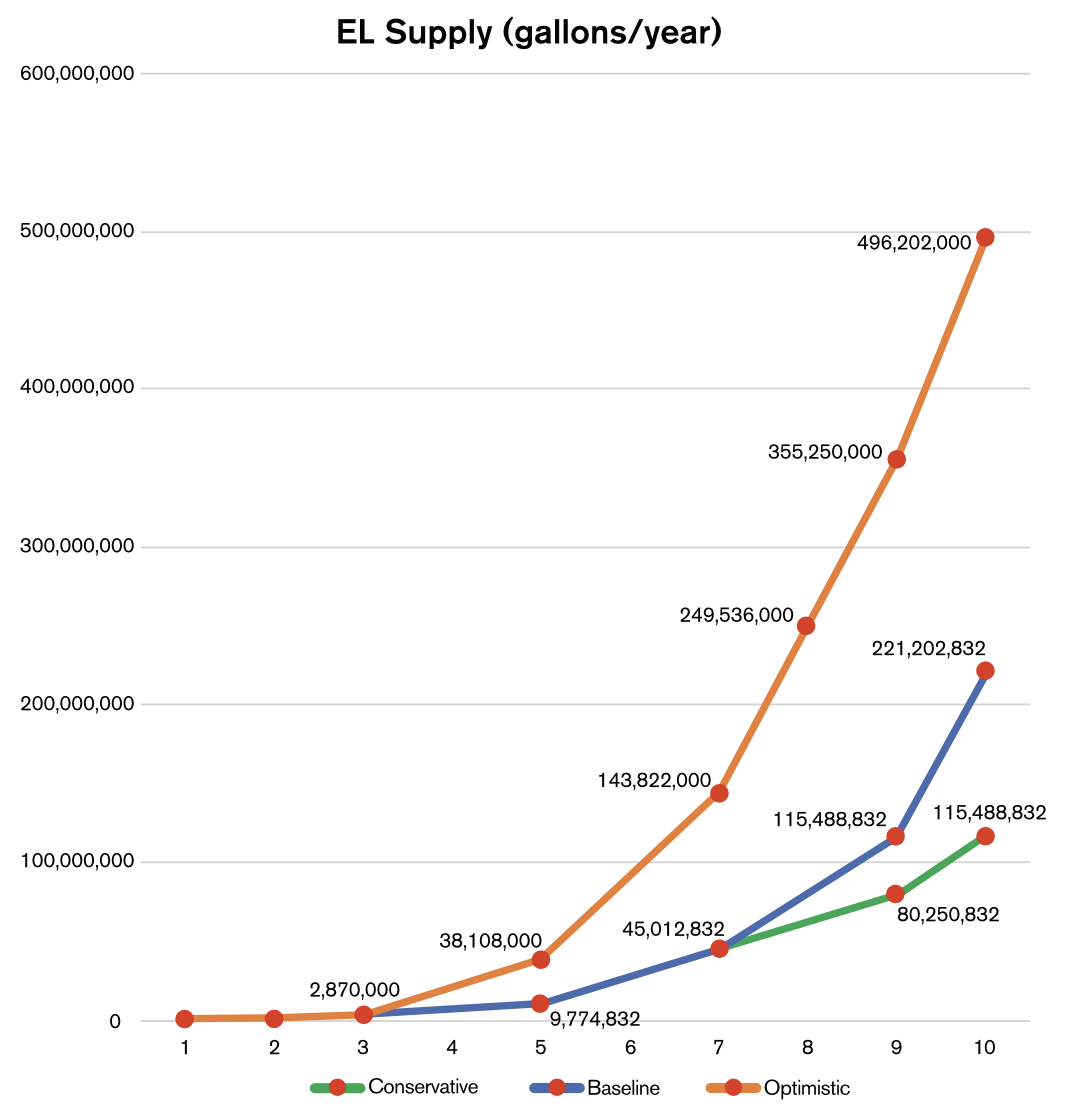

Ethyl levulinate (EL100) is produced from cellulosic (woody) waste biomass – residue on the forest floors, from logging operations, and from municipal solid waste such as paper and cardboard. Biofine Developments Northeast’s proprietary technology processes the biomass to produce a third-party verified, carbon negative biofuel. Biofine is currently developing the first commercial biorefinery, in Lincoln Technology Park in Maine, that is forecast to produce approximately 3 million gallons during Phase 1 (estimated for 2026), and up to 40 million gallons per year once Phase 2 is complete.

EL100 production not only reduces the organic waste on the forest floor that could cause forest fires, but the biochar produced as a byproduct can be used to return nutrients to the soil.

Biofine has been working with the NORA research and development team for more than 15 years, and the product offers the following:

- Excellent cold weather handling

- No cloud point, and does not freeze until -76° Celsius

- Clean burning and efficient

- Lower NOx, lower CO2 emissions

- No SOx, as there is no sulfur in EL

- Works within the existing fuel distribution infrastructure – with minor adjustments

- NEGATIVE lifecycle carbon emissions

- Eligible for D7 cellulosic biofuel RINs and 45Z Tax Credits

NORA and Biofine’s research has determined that EL is not compatible with the Nitrile and Viton elastomers commonly used in fuel oil applications, but works well with Silicon, Teflon and Aflas. When EL100 becomes available market wide, retailers for residential and commercial customers will need to change components and seals – a relatively inexpensive task. Damage to elastomers was seen in tests using an EL10 blend, leading to the conclusion that use of EL100 at that level would require the appropriate system modifications.

Fuel separation was seen in EL blends with traditional #2 oil and biodiesel, and was found to separate at low temperatures. The biodiesel cloud point was only affected to a proportion less than the EL100 concentration, despite EL100’s exceptional cold temperature attributes.

Testing was underwritten by NORA, MTI and the Dead River company. The fuel was stored in extremely cold conditions, with long periods below 0°F. The cost to replace the pump and seal with Teflon products was under $500.00. Additional testing will be done by NORA to assess storage stability, steel corrosion, and cloud point vs Biodiesel content.

EL100 and the Market

Biofine entered into an agreement with Sprague to market and distribute EL100 once it becomes commercially available. At present, the product is receiving strong state and federal support, because the planned construction and end product offer:

- Rural revitalization

- Job creation

- Support of legacy industries, such as forestry and liquid fuels

- Green energy

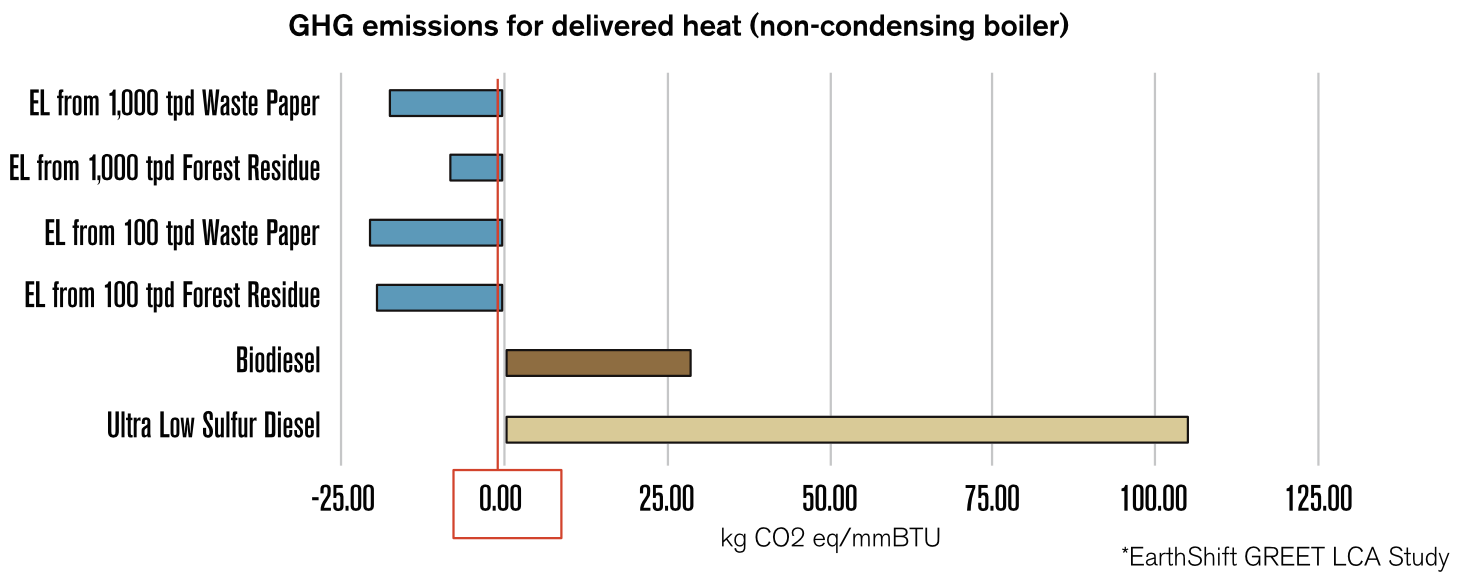

Biofine has had three separate lifecycle analyses performed, in 2012, 2018, and 2022, to confirm its results against changing metrics in how carbon intensity is scored.

The 2022 analysis was completed using GREET 2.0 methodology, measuring all aspects of the fuel, from the collection of bio-mass, trans-portation to the biorefinery, and processing.

According to Mike Cassata, Chief Development Officer, “EL reduces emissions by over 100 percent when compared to ultra-low sulfur diesel. Our proprietary chemical conversion process produces cellulose, hemi-cellulose and lignin. The cellulose is processed to ethyl levulinate, the hemi-cellulose is processed to renewable chemicals, and the lignin is the biochar for energy production or carbon sequestration. The carbon negativity is from the use of waste bio-mass and the replacement of fossil fuels with EL100, the replacement of fossil-derived chemicals with our co-products, and the biochar as a carbon sequestration vehicle.”

EL100 differs from biodiesel and renewable diesel from the start, using cellulosic feedstocks rather than fats, oils or greases. Biofine is focusing on EL’s future as a replacement to liquid heating fuels. “We think it’s a great market for us. We’ve done the work and have a lot of support in the market. There’s no incentive for us to look outside the heating oil market,” Cassata told Oil & Energy Magazine.

“There are a lot of commercial and industrial markets that have very specific CO2 reduction mandates and are trying to figure different pathways to reduce emissions. Reducing fossil fuel use and replacing it with a carbon negative replacement fuel is something that has resonated with them and is very attractive.” he continued.

“We have a lot of strong support from the local, state and federal delegations in Maine. They are very excited about the potential of our product, what it can do for the repurposing of waste materials. State legislators see the role EL100 can play in reducing carbon emissions, which helps the state meet its clean energy goals, and helps private companies and institutions reduce fossil fuel use and meet their CO2 reduction mandates,” Cassata said.

Biofine is also excited at its position within a localized circular economy: the EL100 produced from local feedstock will be returned to the local fuel supply for use in local homes and businesses. They anticipate similar local, circular procurement and distribution cycles for any bio-refineries built in the years to come.

The Lincoln plant will be the company’s first scale-up of the technology, and will provide a blueprint for plants across the country. As one of the most heavily wooded areas in the country, Maine offers many opportunities. Year one of plant operations will require 125 dry metric tons of cellulosic wood waste a day to produce 3 million gallons of EL a year, and Cassata asserts that it’s “not as large a number as it sounds. In the recent past, there were 20 papermills, each consuming thousands of tons of woody biomass per day in Maine.” The Visions Conference presentation noted that 89 percent of Maine’s total area is covered by forest with over 16 million tons of biomass that can be harvested annually and sustainably.

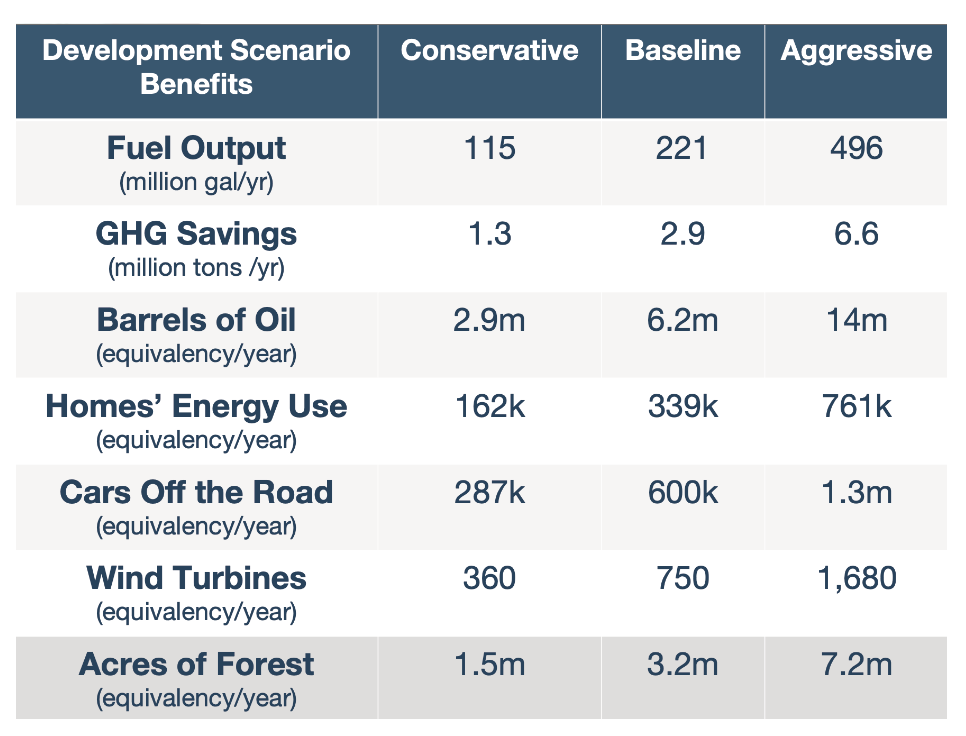

The Phase 1 Lincoln biorefinery is expected to eliminate 73 million pounds of CO2e emissions per year, equivalent to 8,000 passenger vehicles off the road, the home energy use of 4,600 homes, or 8,400 barrels of oil consumed. Longer term, the firm expects to see production of approximately 550 million gallons per year, saving 6.6 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year.

Biofine is in the process of obtaining an ASTM definition, working with NORA, NREL, Beckett and Sprague. Draft ASTM specifications and definition have been developed, and are expected to be completed sometime this year.

Renewable Diesel and Additives

Renewable diesel and other renewable fuels were the focus “An Inside Look at Performance and Benefits of Renewable Fuels,” presented by Leo Verruso, General Manager of Advanced Fuel Solutions.

Verruso took the audience through current low carbon liquid fuel stocks: biodiesel, renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). All three, he explained, are made from similar feedstocks, and “we need them all to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The industry at large needs to evolve and embrace these fuels to mitigate climate change, improve air quality, and enhance energy security and sustainability.

“We need to diversify energy sources and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels. Any gallon of locally produced bio-diesel offsets imports from other countries. It’s not an issue of renewable diesel or biodiesel, we need them all,” Verruso said.

Looking at the different fuels, Verruso reminded the audience that renewable diesel is a hydrocarbon fuel similar to petroleum diesel. In its pure, 100 percent form, there are no aromatics, no paraffin wax (but 100 percent paraffinic hydrocarbon), and a cloud point that could be well below zero. Depending on your cold flow temperature requirements, you would either need to ensure the Cloud Point of the renewable diesel meets your needs, or you can use blends below 20 percent with cold flow enriched distillate. Biodiesel or lubricity additives can replace the lubricity requirements in blends as low as two percent. Lastly, SAF is synthesized from similar feedstocks, but has a specific target market.

Verruso turned to quality control for the fuels, starting with the need for more diligence with tanks with top or side feed lines. The fuel at the bottom of these tanks don’t move, water migrates and settles, and we see microbial growth. This turns into a larger issue in stationary generators where fuel can sit for years before being needed, or residential tanks where the fuel can sit for months. In the diesel market, new engines are more complex and fleets with high idles will have more issues with the exhaust systems and require emergency roadside repairs.

“It’s not the fuels. The fuels are great. The engines are great. But it’s all about what we’re asking them to do, constantly turning them on and off,” Verruso explained.

He continued by reviewing testing of B50 blends in outside tanks in terminal and residential settings, by NORA, Clean Fuels and Hart Home Comfort. These cold storage tests reviewed cold flow additives and anti-settling aids. With the appropriate additive, wax crystals disbursed throughout the fuel, both above and below the pour and cloud points, reducing the chance of sediment or solid wax forming. Additives such as these are not only for home heating, but also help diesel vehicles warm up and be road ready more quickly.

Verruso repeated the instruction to “inspect what you expect” and to fix the problem, not the issue. Rather than simply fixing a no-heat call, he urged the attendees to train their staff to find the source of the no-heat call. Was it a gelling or flow issue? Was there sediment in the tank? Retailers need to play an active role in maintaining fuel quality: ensuring the fuels are dispersed from and into a clean vessel; sticking tanks and conducting bottom sampling; occasionally testing your fuels and additives by either sending them out, or simply putting them in a freezer; keeping records of deliveries and service calls; training employees to reconfigure two-pipe systems to a single pipe; and, most of all, be consistent and committed to excellence.

Biodiesel. Renewable diesel. Ethyl levulinate. Each offers an opportunity and a path to net-zero and even negative emissions. As Verruso said in his presentation, “It’s an all of the above, not an either/or solution.”