Are combustion powered heating systems the cause of poor IAQ?

Indoor air quality has become a newsworthy topic as certain pollutants have been identified as health hazards by, among others, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It has been suggested that combustion powered home heating appliances are some of the sources of these indoor pollutants. As combustion powered heaters make up almost 75% of all heating appliances, NORA deemed an investigation was in order.

Of particular interest is particulate matter (PM), which is known to have both human health and negative environmental impact. NORA, at its Liquid Heating Fuels Research Center in Plainview, NY, took a deep look into PM in home living spaces to determine whether liquid fuel combustion devices negatively impacted indoor air quality.

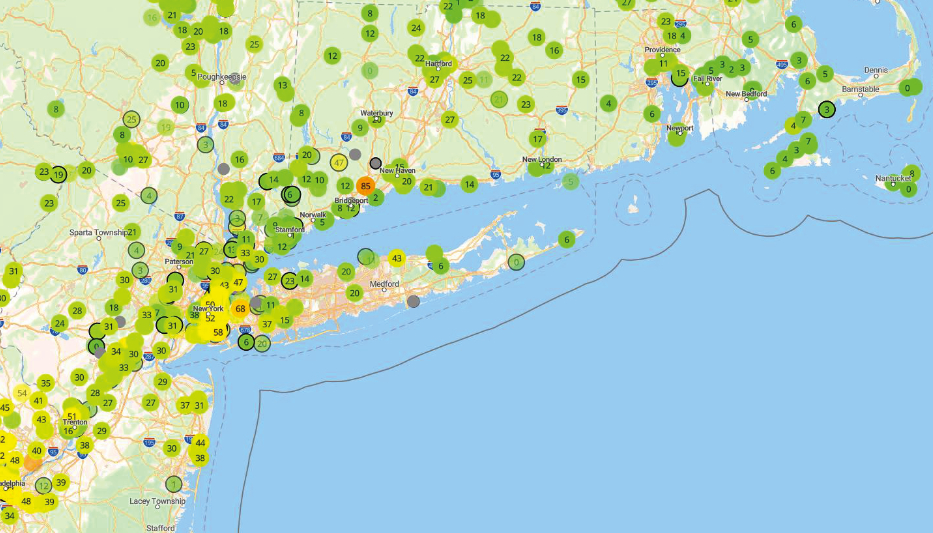

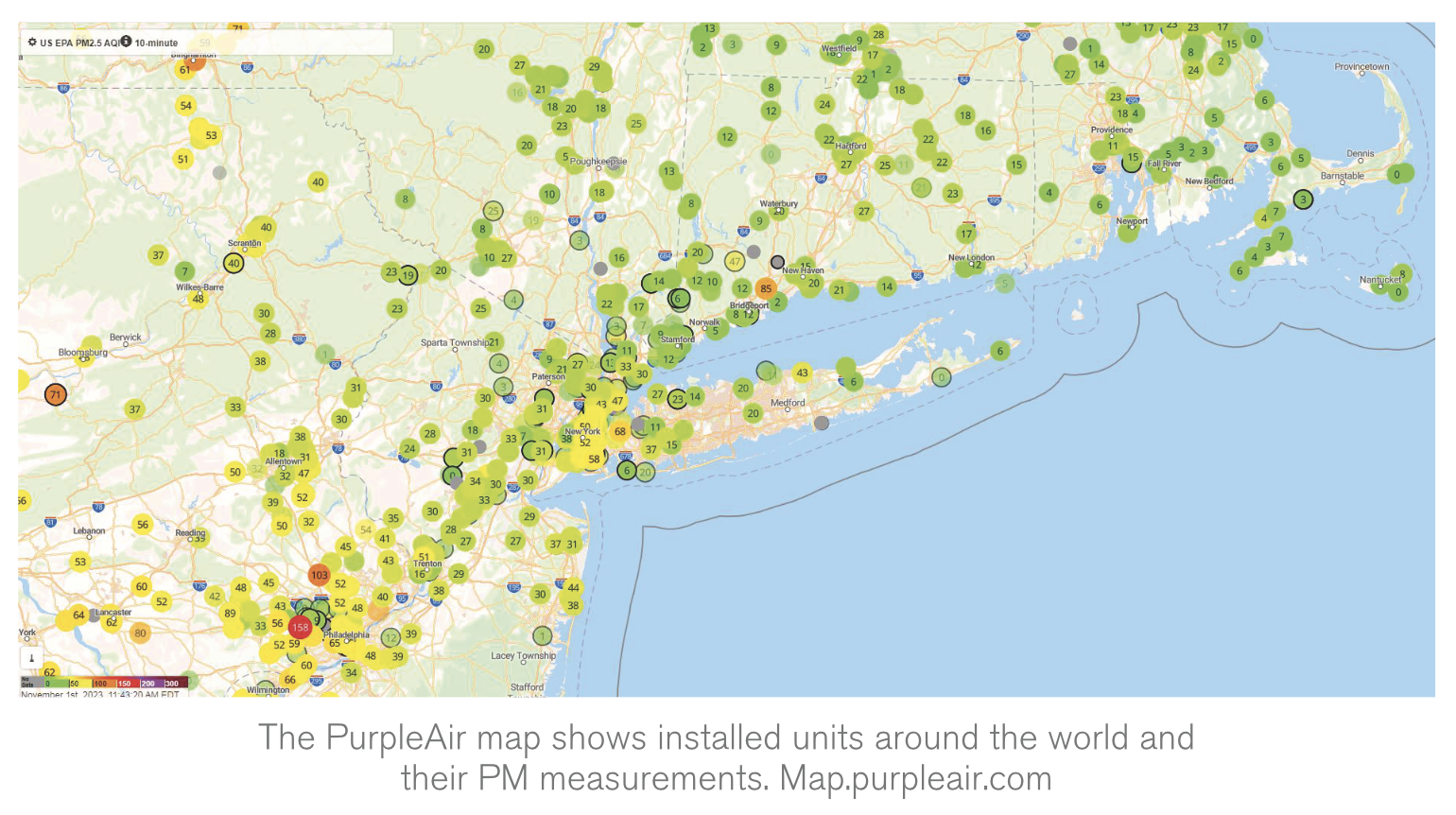

Fortunately, a low-cost and effective method of measuring PM has recently entered the marketplace. Named PurpleAir sensors, these devices measure PM, PM2.5 and PM10 (the subscripts denote the particle sizes in micrometers [µm]) in micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), which indicates the actual amount of particulates found in the air. Using dual laser-based particle counters, they can measure particles larger than 0.3 microns with counting efficiency, reported by the manufacturer to be 50% at 0.3 microns and 98% at > 0.5 microns.

Test Sites

The PurpleAir units can be installed to perform stand-alone, storing its readings offline, or connected to the internet to display the PM2.5 concentrations at its location on a worldwide map of an increasingly expanding network. For the NORA study, only offline measurements were used in houses with primarily a liquid-fuel-fired heating appliance. Eight homes—five in NY, two in MA and one in NJ—were chosen for this study. Seven of the eight were selected because they contained a liquid-fuel-fired heating system. The other was chosen to record data in the den area (kitchen and living room with a fireplace) during a time when the homeowner planned to cook and light a fire in a wood stove. A set of PurpleAir sensors was provided for each home. Typically, at least one indoor and one outdoor sensor was installed in each site. Four of the sites were fitted with a flue gas measurement sensor to indicate when the heating system was running.

Liquid fuel-fired boiler and furnace installations typically include barometric dampers, which are draft-operated “doors” that open to allow room air into the flue pipe to prevent high draft levels. High draft levels can change burner air fuel ratio and, in an extreme case, can destabilize a flame. Modern burners for liquid fuels have higher static pressure fans and are less influenced by these draft changes, but barometric dampers are commonly found in many installations. Barometric dampers may be a potential source of indoor air pollution as flue gas could spill into the room during startups. While this does not usually happen with modern equipment, the Purple Air sensors were placed as close as possible to the site barometric dampers to record possible spillage.

Correlation of PM Spikes

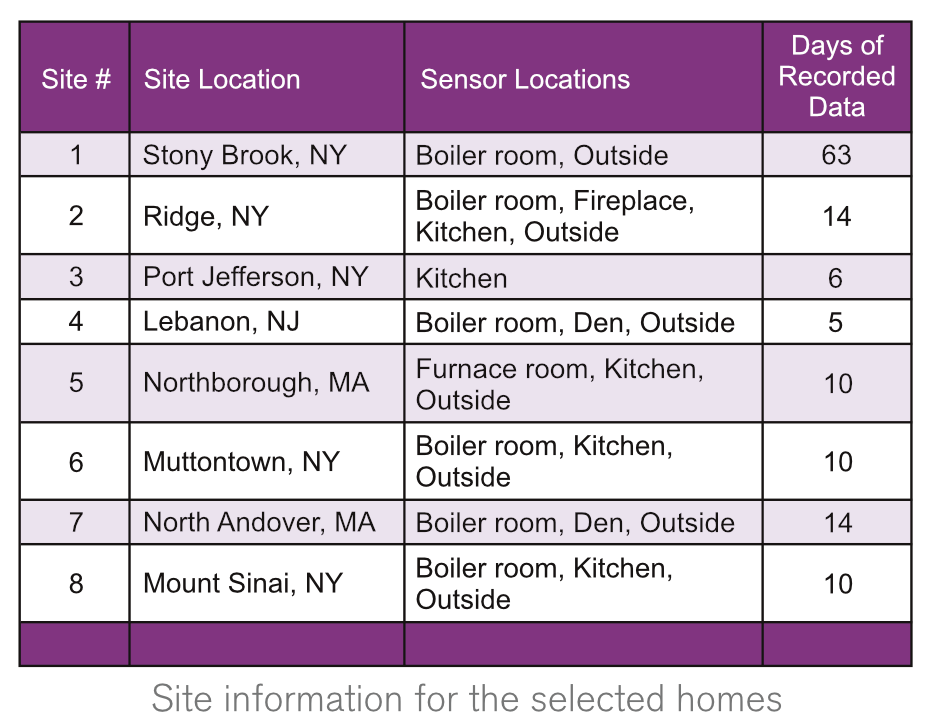

For some of the sites, the boiler room was found to have periodic spikes in PM2.5, but when paired with the “on” measurements of the flue gas sensor, it was shown that the heating system operation did not correlate to these spikes. One example is shown in Figure1, where you can see a plot of the PM2.5 concentrations (left y-axis) and the flue gas temperature (right y-axis) and the time (x-axis) over 24 hours. During this period, there was a major peak (close to 450 µg/m3 in PM2.5) concentration observed in the boiler room where the PurpleAir sensor was located approximately six feet from the boiler flue pipe. Upon consultation with the homeowner, it was found that he had performed soldering of metal pipes without ventilation in the boiler room. The flue gas temperature readings show the boiler was not operating nor did it operate during a period of approximately four hours before and approximately 12 hours after the soldering took place.

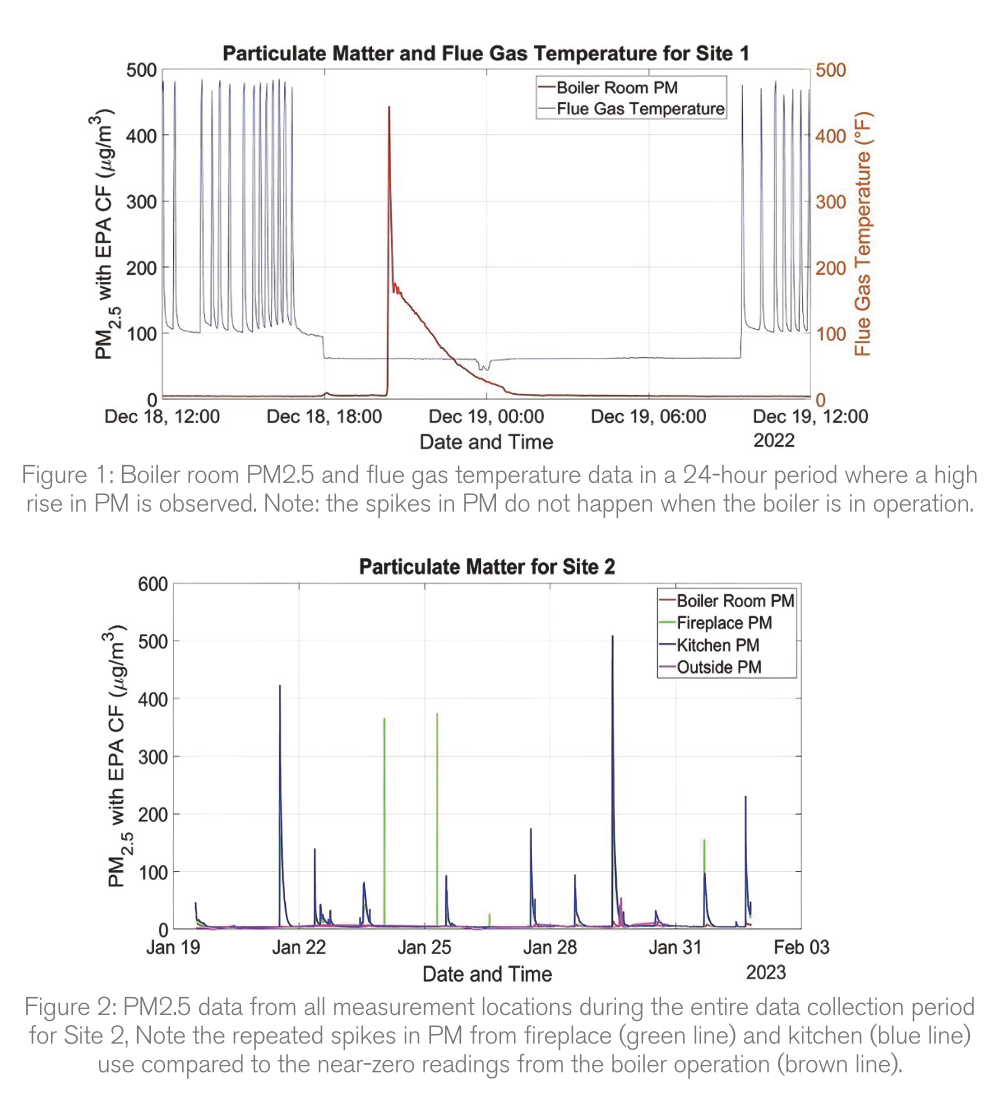

It was also found in the data from other sites that cooking and fireplace use had a major impact in indoor PM2.5 concentrations. Additionally, outdoor grilling also caused rises in indoor PM2.5 concentrations when doors and windows were left open to allow particulate matter to enter the home.

In the example illustrated in Figure 2, indoor cooking and fireplace activity (green and blue lines) caused major spikes in PM2.5 concentrations, while the sensor in the boiler room remained at near zero. This look into combustion from liquid-fuel-fired heating systems was found to have no significant impact on indoor air quality as was indicated by the PurpleAir recording of particulate concentration. Other indoor combustion activities, and use of wood heating in the area around the home sites, were found to produce elevated levels of indoor PM2.5 concentrations within the specific homes being monitored.

These results are important as they indicate combustion in properly operating liquid heating appliances does not impact indoor air quality. To improve the health and safety of home dwellers, other household activities, such as cooking, fireplaces and outdoor grilling should be carefully examined.